Snapshot

- India needs to build a strong public transport system and keep multiple options open rather than blindly investing on the EV ecosystem.

When NITI Aayog was gearing up for the Global Mobility Summit in Delhi, a video of a `bicycle bus’ in The Netherlands was doing the rounds on WhatsApp. It featured an open bus, propelled forward by schoolchildren, excitedly peddling away at their individual pedals. Several such buses were moving on the road in the morning along with other assorted non-motorised transport (NMT) in special lanes, which had priority at the traffic lights. It was overall, a delightful, refreshing sight. “Not possible in India, given our potholed roads and chaotic traffic!” – was the common refrain at the end of the video, despite the glee and wistfulness that had accompanied the watching.

Incidentally, the agenda of the high-profile Mobility Summit in the capital was to “evolve a clean, efficient, safe and inclusive transport system”. While many were expecting a roadmap for electric vehicles (EVs) from the event, which concluded a little more than a week ago, it stopped short of that.

What emerged was that India is in the process of deciding which road to take in mobility. NITI Aayog Vice Chairman Rajiv Kumar explained in an interview to ET Now: “The idea of the summit was to learn, and not to make announcements. Having invited high-profile people from across the globe, it would have been presumptuous to announce a policy”. With all inputs in hand, reportedly, now a policy will be formulated that would bring all relevant ministries together, as also plans to coordinate with state governments.

Though some are disappointed that the summit did not come up with tangible measures on EVs, that EVs are still priority for policymakers is evident: NITI Aayog’s Kumar mentioned in the course of the two days: “we need to put a date to it, say by 2047, the 100th year of Independence.” So, EVs, driven by renewables – appears to be the direction we are broadly moving in, in transport.

Glaring Blackholes, But Atmosphere Is Still Electric

EVs fit in with global transport solutions to reducing greenhouse emissions and combat climate change. They are alternatives to petrol and diesel transport, so they also help reduce dependence on fossil-fuel imports that make countries vulnerable to oil price shocks, and add to import bills. Energy security and fighting pollution are significant causes, too.

Thus, EVs have come to be the solution of choice.

But India’s frequently-changing stand in this area has left many puzzled (and top-league car-makers, disgruntled): In the getting-carried-away stage in 2012, the targets were ambitious at 6-7 million cars by 2020, as per the NEMMP (National Electric Mobility Mission Plan) 2020. In 2015, Faster Adoption and Manufacturing of Hybrid and Electric vehicles (FAME) was brought in for rapid adoption. Then, at some point there was a target of “100-per cent new vehicle sales by 2030”, which came down to “40-per cent by 2032”; early this year, it was announced that there would be no special policy for EVs.

The reason for the rethinks on targets is the bumps experienced along the way. Reasons that underline the country’s unpreparedness to launch a major move towards the programme include costs (both initial and battery), range anxiety (EVs can run only limited number of kilometres on the fully-charged battery), lack of charging infrastructure, and other perceptions – from the point of view of individuals.

From the point of view of the country, too, the economics doesn’t work out. A study by IIMA on Electric Vehicles Scenario in 2014 pointed out that to become competitive, EVs need to be supported by fiscal concessions like sales tax, duties, etc. The analysis found that if the capital costs of EVs were brought down by around 30 per cent, only then would a major shift to EVs happen. However, the revenues that government would need to forego to provide this support would be Rs 2,803 billion for the period until 2035!

Loss of revenue (Rs billion)

Apart from initial costs of EV, battery costs are prohibitive. India does not have enough lithium to manufacture lithium-ion batteries that power EVs. The current dependence is on China, and even if we were to establish a reliable supply chain from other countries also, it would only lead to substituting imports of one form of input for another (lithium battery, instead of crude oil). What then of the country’s stated intentions of energy security and reducing import burden? Says former secretary, MNRE, Deepak Gupta, “We should not replace oil imports with battery imports. This is applicable to both EVs and solar energy.” Importantly, lithium is also a limited resource.

Cheaper substitutes for lithium have yielded poor-quality batteries, which proved to be a deterrent to people making a shift to two-wheelers. In 2011, the government did manage to sell 1.2 lakh two-wheelers – subsidy on the vehicles – but post withdrawal of subsidy and owing to battery quality, sales plummeted to 25,000 by 2016. This past experience makes us wonder how policymakers are still betting high on the two-wheeler segment to take to EVs. Reports from a user in Hyderabad additionally cite as deterrents loss of power when going up slopes, or with a pillion rider in tow.

Adopting EVs in public transport such as bus fleets is also beset with the same issues – battery prices, weight of the large batteries, charging infrastructure that requires huge investments (and runs only because of government subsidy, the world over), long battery-charging times, and limited range of driving. Battery swapping, the viable alternative is going to be expensive. Yet, it is being assumed that this sector will be able to absorb costs over five years – the big assumption being that battery costs will come down 20 per cent by 2020. Also, in relative terms, as the BS-VI norms will make owning diesel and petrol vehicles costlier, as this EY report explains, it can be concluded that much of the planning hinges on ifs. In such a scenario, planning for an EV-centric policy is a bit like shooting in the dark,especially when such huge expenditures are required in advance. Just for illustration, an e-bus costs Rs 1.5-2.5 crore, and a battery costs Rs 50 lakh upwards (with a life of seven-10 years).

The proposition is also risky because of these factors: one–disposal of used lithium batteries is environmentally hazardous; two – high dependence on the electrical grid supply for charging would make it inefficient (until renewables take off in a big way); three –dependence on electrical grid supply would also make EVs prone to disruptions from power outages; four – if the energy on which EVs are dependent for charging comes from “unclean” sources, the purpose is defeated; five – the import bill would still be high; six –international experience is not encouraging i.e. after several years of adoption in other countries, EVs still run on subsidies; seven – lithium is also a limited resource!

Does it make sense to put all our eggs in the EV basket then?

Why Is Hydrogen Being Ignored?

It’s interesting that hydrogen (H2) fuel cell ecosystem does not find mention in India’s mobility planning. One reason for going full-steam ahead with EVs could be the collaborations with Boston Consulting Group or BCG (which did a volte face and suddenly discovered affection for EVs last year), and the ACEEE (American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy), which draws up the international energy efficiency scorecard, and which helped India design its energy efficiency index released last month.

However, the fact is that the jury is still not out on which is more efficacious, H2 or EVs, with ardent supporters and defenders of both. Hydrogen fuel, too, has the advantages of being low-carbon; but it has advantages such as being not deplete-able, is free of range-anxiety and charging-time anxiety, as it refuels within minutes. Importantly, it can also run on internal combustion engines (ICE), which will not need to be replaced if hydrogen is adopted – unlike the EVs. This single benefit outweighs all others: the current ecosystem is built around ICEs, and the employment it provides to the entire auto industry would remain undisrupted.

Certainly, there are issues with costs and transportation of hydrogen too; yet, there are also suggestions to overcome these. Going into technical details is beyond the scope of this article, however given that it is catching on in countries like Germany, Australia and Japan, and Toyota, Hyundai and others are manufacturing vehicles based on H2 suggests that there is reason to not dismiss it right away. Even last year, Indian Space Research Organisation former chairman, G Madhavan Nair had emphasised that hydrogen is the future: “In the long run,hydrogen-based thing will be the right choice because hydrogen has to become the fuel of the next generation.” Nair had cited disposal of lithium batteries and their handling as causes for worry, and his suggestion was to go for more research and development in India to generate hydrogen in an economical manner. ISRO and Tata Motors had developed a hydrogen-powered bus in 2013.

MNRE’s steering committee on hydrogen energy and fuel cells had, in fact, put out a study on this in 2016. Citing the examples of several countries and companies, it had recommended that development and demonstration of a fleet comprising of 10 cars, 10 two-wheelers, 10 SUVs, 10 three-wheelers and 10 buses operating on fuel-cell technology be taken up as a mission mode project along with 10 dispensing stations in different places. It had even suggested supporting this through a `Centre of Excellence’ in IOC R&D.

This option must be tried out simultaneously, given the uncertainties and inherent flaws already perceptible in EVs. A good place to start can be in green field smart cities.

De-motor, Decongest, De-clutter

In connection with the Summit, a report titled Transforming India’s Mobility: A Perspective was brought out by BCG-NITI Aayog. This was a comprehensive look at India’s specific issues in transport and mobility: Connectivity across rural and urban areas; cleaner technologies that reduce our emission and carbon footprint; reduction of pollution in cities; efficient public transport system, among others.

An interesting takeaway was the role of non-motored transport (NMT). Motor vehicles, as we know, are the biggest contributor to pollution, and 10 out of the top most-polluted 20 cities in the world are in India. Given below are some cities’ pollution levels.

A sense of responsibility demands immediate steps to address this issue – and those cannot come from either EVs or hydrogen fuel, as these require massive updates in infrastructure and manufacturing. What is in the government’s hands, which would be a sure shot mitigator of pollution, is the use of non-motor vehicles and – human limbs. Both need to be encouraged.

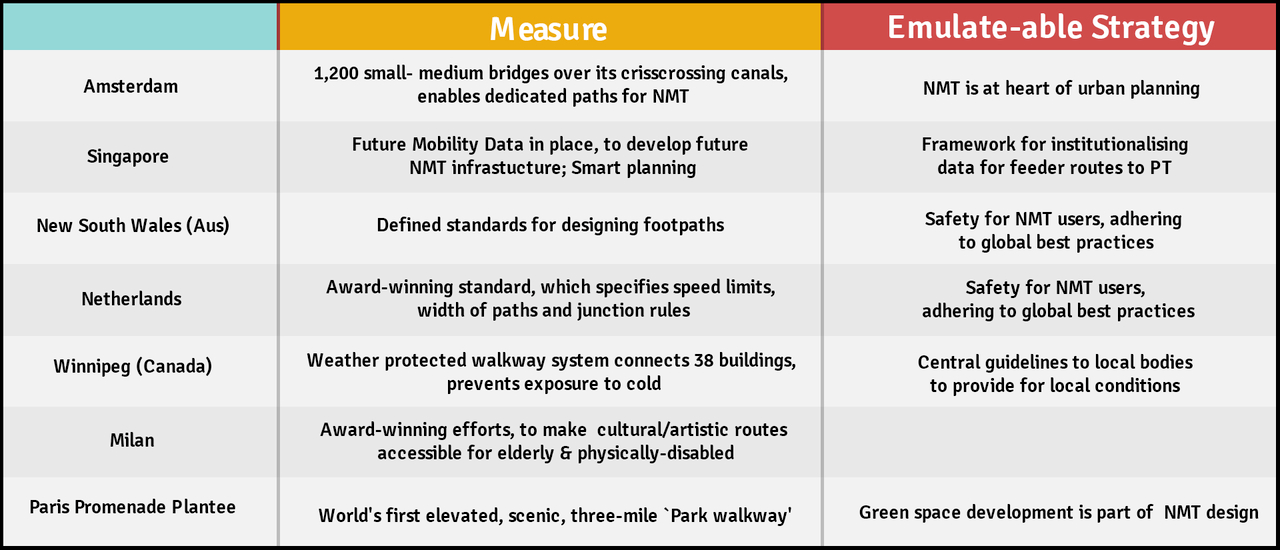

If funds for incentives and investments for EVs can be made available, can’t some amount be used for creating lanes for cycles and bicycle buses in cities? Perhaps, also wide, tree-dotted, well-groomed pavements and sidewalks that make walking a pleasure? Perhaps, flyovers for motor vehicles and good strolling lanes at ground level for walkers? Hyderabad has an 11-km flyover to ease congestion; why not plan several such flyovers that would help free roads for pedestrians? Alternatively, elevated walkways – an example being the Promenade Plantee in Paris. Some such global examples and strategies that can be emulated were outlined in the BCG report, as given below:

Global NMT examples

We need to plan cities in a way that a combination of public transport, non-motor transport and walking would not just be attractive – but in fact, would make using private vehicles a foolish option. The latter two modes would add another ‘C’ – cost-effective/C=cheap – to Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s path of “The 7Cs: common, connected, convenient, congestion-free, charged, clean, cutting-edge”. Make using private cars superfluous for any reason – simple!

The Smart Cities Mission helmed by urban local bodies is a good place to begin. Net-net, this will turn out cheaper than investing huge resources in new technology. Creating public awareness will be an important ingredient in this, and that will include inculcating the healthy habit of walking in the younger generations.

Multi-Modal, Multi-Fuel, Multi-Option

EV technology would be well used in three-wheelers; e-rickshaws are in fact, best placed to bring this technology into, as they have relatively low initial costs, are automatically low-range vehicles and easier to charge at home. Besides, this is an area that is a genuine and legitimate beneficiary of government subsidy – for the sake of employment and income-generation. This also fits very well with the crucial last-mile connectivity from public transport points like metro stations and bus stands.

Ultimately, we’re suggesting investments in a strong public transport system; bus fleets to be eventually run on hydrogen, while metro trains and three-wheelers run on electric ecosystems, and infrastructure for bicycle buses, cycles, walking – lots of these. There is reason to set aside funds for all these avenues – rather than invest blindly on the EV ecosystem. Since we are making a clean start, may as well keep it multi-option too. This, the mobility policy must keep in mind.