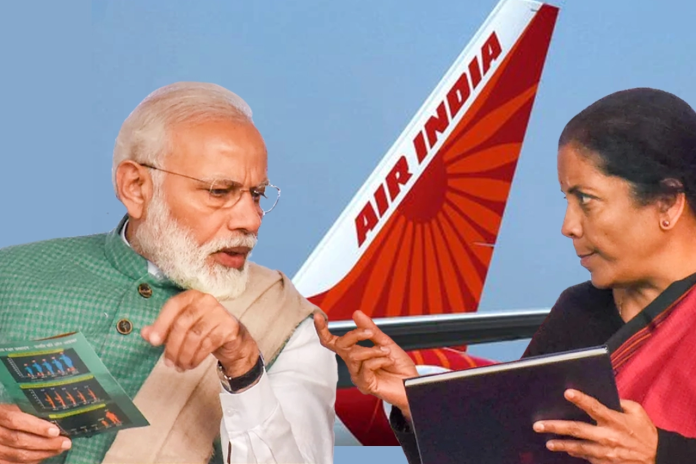

On Jun 27, Ministry of Finance extended the deadline for the bids for Air India to August 31, from the earlier announced date of June 30. Yet despite proclamations of it being a valuable asset, industry sources indicate that it is down to one buyer. This itself is troublesome and in other times may have forced a rethink.

With slowing economic growth, an impending liquidity crisis and the spread of Corona Virus, questions are being asked whether the sale of Air India in such an environment is a correct focus area. After all won’t the exchequer realize a far lower value given that cash-flows have dwindled and asset values are at an all-time low. But the numbers illustrate why the sale of Air India is the only option left for the government.

Sunk costs of INR 24,000 crores

From 2014-15 to 2018-19, the union government invested more than INR 24,000 crores in Air India. This investment was aimed towards both achieving operational sustainability and effecting a turnaround. But the balance sheet continues to remains weak and much of this cash was consumed in ongoing operations. Consequently the results of this infusion on costs, on revenues or even on product are non-existent.

It is may be noted that with the same amount of money that has been put into Air India revival, a new airline could be established. And herein lies the challenge. Because investors are always looking at alternatives. And currently those include sitting on the sidelines, setting up a new airline or waiting patiently for a Jet Airways like situation and acquire only select accretive assets.

To compete Air India needs to cut its costs by INR 10K crores — annually

Air India requires a extremely drastic approach to cost-cutting. Pre-Covid estimates were that the airline is losing INR 15 – INR 20 crores per day and with fleet strength of 124 airplanes this was unsustaniable. During Covid, in spite of Vande Bharat flights, this has likely become worse – because Air India has taken very little action on the cost structure. And with demand down by upto 60% the revenues simply cannot cover costs.

As the skies open up, to even come close to competing, Air India needs to attack its cost per available seat kilometer (CASK) which is the key measure of success for airlines. Its current CASK is 18% – 22% higher than competitors. As such they can simply discount and take traffic from Air India or match prices and be profitable while Air India bleeds. In either case, the unpleasant reality of costs not being competitive has to be attacked. The question: who will drive this reduction and how?

With a management team where seniority carries more weight than merit coupled with short management tenures in senior-most roles , the cost cutting goal remains elusive.

Balance sheet restructuring requires skin in the game

Air India carries on its balance sheet consolidated carried debts of Rs ~58,351 crore. This in any form unsustainable. The government stepped in and drastically reduced this debt to Rs ~23,286 crore of debt moving non-core assets to a special purpose vehicle named Air India Asset Holding Ltd (AIAHL).

Even so, the balance sheet remains weak and the only reason lenders are extending credit is because of sovereign guarantees.

To service this debt requires cash-flows. And the cash is just not coming in in the proportion it needs to. With a net loss of Rs 7,635 crore for FY19, the airline requires access to credit of between INR 10,0000 to 14,000 crores – annually. This figure does not include working capital shortfalls and provisions.

The spread of the corona virus has led to drastic falls in demand and at a time where Air India should be announcing significant capacity and cost cuts all one hears is silence.

Balance sheet restructuring requires management with skin in the game and that is just not the case.

No cash for additional investment in fleet, product and network

Air India is currently flying a fleet mix of 124 aircraft powered by five different engine types (excluding sub-types). Majority of the fleet ~65% is narrow-body aircraft with the balance being wide-body aircraft. And of this 75% of the fleet is already leased with lease terms that are not quite competitive. Add to that the fact that the fleet is not mission specific which presumably derives from how the fleet orders were put in. In this scenario, renegotiating the contracts is the way to unlock additional value. Yet again the question remains: who will drive this reduction and how?

Due to the cash-flow situation at the airline, the on-board product has not been upgraded and is waiting for additional investment. This investment would be over and above the cost savings and balance sheet restructuring and assuming the product upgrade only happens on aircraft flying international routes the amount is north of INR 700 crores at the minimum.

Finally the strategic overhaul requires talent that is empowered and can deliver on a core plan. That is, the airline requires talent that understands market dynamics, which understands socio-political dynamics and is empowered with a clear mandate.

Misaligned incentives and preference falsification

Assuming a scenario where a sale is postponed or even cancelled, the government is in a tough situation because they have publicly and strongly committed to a goal of disinvestment and also because there is simply not enough money in the system to continue to fund Air India.

But even casting all this aside, and assuming more equity infusions are done, a turnaround at Air India requires all stakeholders to be aligned towards a single outcome. That outcome: a profitable airline. Unfortunately, in spite of key assets and advantages this has simply not happened. Rather, there is abundant preference falsification

The term preference falsification was coined by Professor Tim Kamur of Duke University. It captures the fact that while stating preferences there is a tendency to gravitate towards what is socially acceptable or least risky reputationally even while this may be in contradiction to true belief.

In the case of Air India, its leaders have been responsible for the airline but accountable to the political executive. And while diverse leaders have indicated that the airline should be shut-down or sold, the political risk, the reputational risk and the social risk has been fairly high. After all 20,000 employees equates to more than 40,000+ votes; an airline failure is almost certain to make headlines for several years (much like the Kingfisher and Jet Airways debacle); and the Air India brand continues to be one of the strongest and easily recognizable brands so no one wants to be responsible for killing the brand.

Thus while speeches and memos often indicate that several actions will not be tolerated, when it comes to affecting deep structural changes in the airline, there has been no action. Quantitatively this is reflected in the financials, qualitatively in the customer perception and operationally metrics such as on-time performance and fleet utilization.

Drastic action has just not been taken. After all, no one wants to be at the helm of a strike or at the helm of a grounding or at the helm of a shutdown. Preference falsification is a convenient alternative.

Air India, a once proud carrier stands crippled due to a confluence of factors. News reports indicate that there may be a sole bidder for the venture. This all or nothing bet does not bode well for the government. But with no more funds coming, a sale is the only option.