The security of maritime chokepoints worldwide is once again a major concern for energy markets.

This comes after the Iran-aligned Houthi rebels of Yemen seized control of a car carrier named Galaxy Leader, traveling from Turkey to India, in the Red Sea on Sunday (19 November), raising fears of another dimension being added to the ongoing Gaza conflict.

Despite Israel’s firm denial of ownership or operation of the ship and its insistence that none of the crew members hold Israeli citizenship, evidence suggests a connection to an Israeli billionaire.

According to AP, “ownership details in public shipping databases associated the ship’s owners with Ray Car Carriers, founded by Abraham “Rami” Ungar, who is known as one of the richest men in Israel.”

The occurrence has reignited concerns that the Israel-Hamas conflict might trigger substantial disruptions in shipping along critical maritime chokepoints in the Middle East, something which hasn’t happened so far.

The Lifeblood of Global Commerce

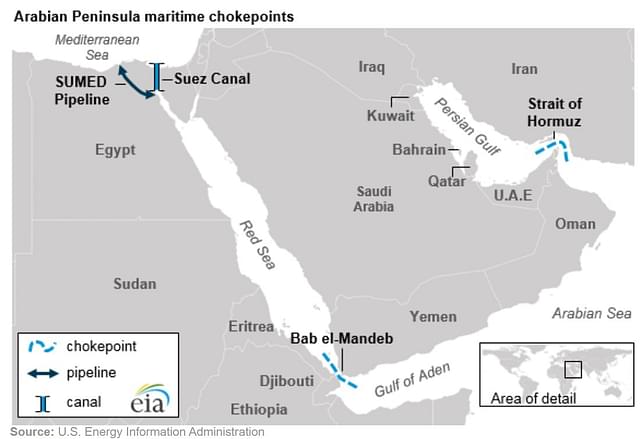

Maritime chokepoints are narrow channels connecting two bodies of water along widely used sea routes. Some of these are so narrow that restrictions are placed on the size of the vessel that can navigate through them.

Historically, many chokepoints served as strategic geopolitical assets for the nations overseeing them. In contemporary times, these assets are overseen by independent authorities that operate like businesses under commercial pressure and principles – which means it is in their interest to keep traffic flowing.

Some of the world’s most important corridors include the Panama Canal, the Turkish Straits, Bab-el-Mandeb Strait, the Suez Canal, and the Straits of Malacca and Hormuz.

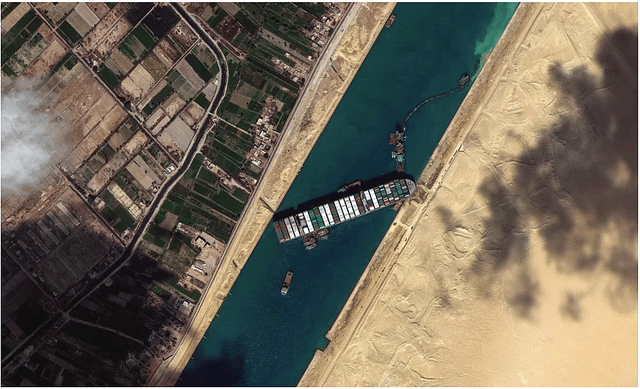

Possibly the most telling example of how global trade is interconnected through chokepoints comes from March 2021 blockage of the Suez Canal.

In March 2021, the container ship Ever Given blocked the Suez Canal for six days, holding up nearly $775 million worth of goods on the ship and sending shock waves through global supply chains.

The Energy Centre

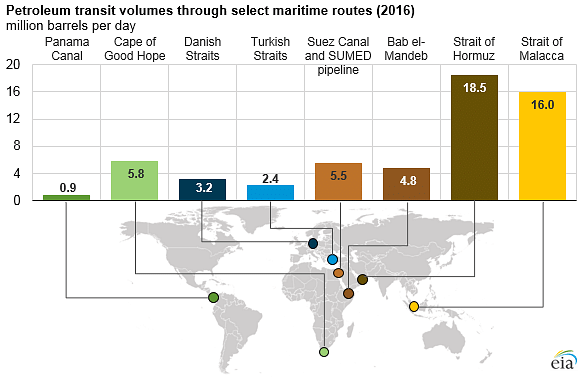

To grasp the extent of our energy supply’s reliance on the unimpeded movement through these chokepoints, and the ease with which disruptions can occur, an examination of the data is imperative.

The most significant among the 14 major chokepoints globally is the Strait of Hormuz, which allows vessels direct access to the otherwise closed-off Persian Gulf.

According to the US Energy Information Agency (EIA), the Strait of Hormuz carries approximately 30 percent of the world’s crude oil and other liquids, along with 30 percent of global LNG trade.

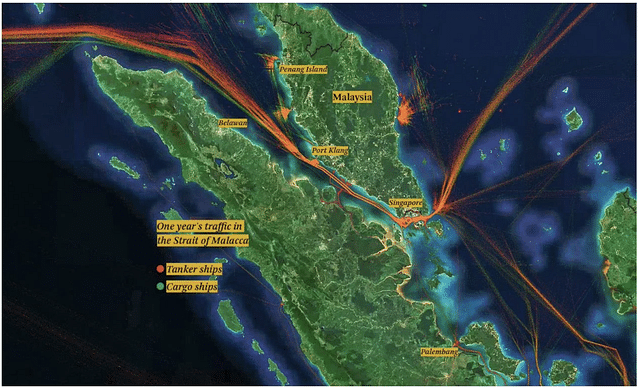

Similarly, the Strait of Malacca — a vital sea route connecting Persian Gulf suppliers to Asian markets like China, Japan, South Korea, and the Pacific Rim — handled about 16 million barrels of crude oil and 3.2 million barrels of LNG in 2016, making it the world’s second-largest oil trade chokepoint, following the Strait of Hormuz.

Put simply, Chokepoints are a critical part of global energy security because of the high volume of petroleum and other liquids transported through them, the disruption of which could easily throw the global energy market into disarray.

Therefore, the inability of oil to transit a major chokepoint, even temporarily, can lead to substantial supply delays and higher shipping costs — resulting in higher world energy prices.

Chokepoints also expose oil tankers to vulnerabilities such as theft from pirates, terrorist attacks, political unrest in the form of wars or hostilities, and shipping accidents that can result in disastrous oil spills

The Israel crisis

The hijacking by Houthi rebels aligns with their previous declaration, where they stated that they would target Israeli vessels in the Red Sea and the Bab al-Mandeb Strait should Israel persist in its actions leading to bloodshed in Palestine

“Our eyes are open to constantly monitor and search for any Israeli ship in the Red Sea, especially in Bab al-Mandab, and near Yemeni regional waters,” Yemen’s Houthi leader, Abdulmalik al-Houthi said in a broadcast speech.

In a further escalation of the threat, Mohammed Abdul-Salam, the chief negotiator and spokesperson for the Houthis, declared in an online statement, “The detention of the Israeli ship is a practical step that proves the seriousness of the Yemeni armed forces in waging the sea battle, regardless of its costs…This is the beginning”.

No wonder, the impending threat to global shipping lanes found resonance in a statement released by the Prime Minister’s Office of Israel on Sunday.

“This is another act of Iranian terrorism and constitutes a leap forward in Iran’s aggression against the citizens of the free world, with international consequences regarding the security of the global shipping lanes,” Benjamin Netanyahu’s office said.

What Lies Ahead

The potential for a global energy shock following Hamas’s aggressive assault on Israel has become a significant concern for economists and policymakers who, over the past year, have been trying to combat inflation.

A report from the World Bank, released last month, has already indicated that oil prices could surge by as much as 75 percent in the event of a significant escalation of the conflict between Israel and Hamas.

“The latest conflict in the Middle East comes on the heels of the biggest shock to commodity markets since the 1970s — Russia’s war with Ukraine,” Indermit Gill, the World Bank’s chief economist and senior vice president for development economics, said in a statement that accompanied the report.

“If the conflict were to escalate, the global economy would face a dual energy shock for the first time in decades — not just from the war in Ukraine but also from the Middle East.”

Houthis involvement in the conflict is more than just a signal to Israel and the seizure of the car carrier is a political signal that the transit through maritime chokepoints could be easily weaponised, says Francesco Sassi, a Research Fellow in energy geopolitics and markets.

As such, it was not by accident that global oil and gas prices reacted bullish on the news of the ship hijack, adds Sassi.

What is clear at this point is that unless we recognise the burgeoning threats to our complex supply chains, the likelihood of a serious breakdown is not a question of if, but rather a question of when

“Unfortunately, it usually takes a crisis to happen before we take appropriate action,” says Richard King, senior research fellow in the Environment and Society Programme at Chatham House, a British think tank.

“It’s probably going to take a series of shocks to nudge us in the right direction, and we’ve got to be hopeful that those shocks are manageable rather than being truly catastrophic.”