- India has finally learnt the art of leveraging the size of its market for its own best interests.

A week before the release of the national economic survey is an excellent time to review India’s most vital sector — the import of oil and gas. Since we are heavily import-dependent, it is the fulcrum of both our economic growth and the geopolitical dynamics we have to face.

The calendar year 2023 saw a stagnation in the import of crude oil and liquified natural gas (LNG). The import of LNG, for example, is yet to recover to pre-pandemic levels. But what has changed is the pattern of their sourcing.

This data also reconfirms a trend that evolved over the past decade: India has finally learnt the art of leveraging the size of its market for its own best interests.

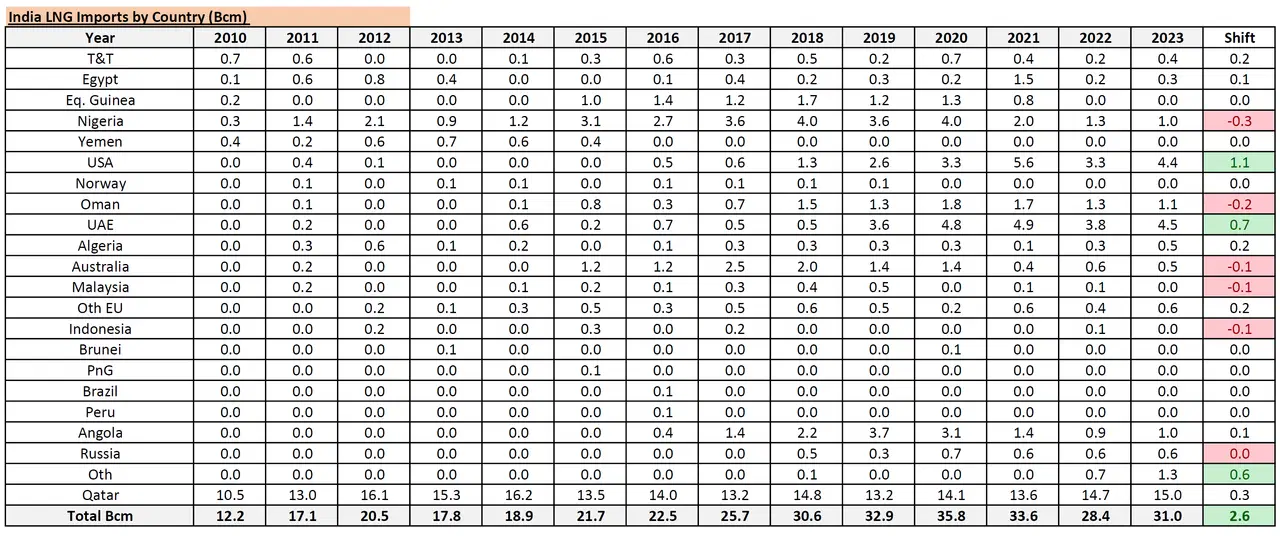

This article focuses on gas imports, and a table of country-wise sourcing of volumes since 2010 is given below. Units are in billion cubic metres (bcm).

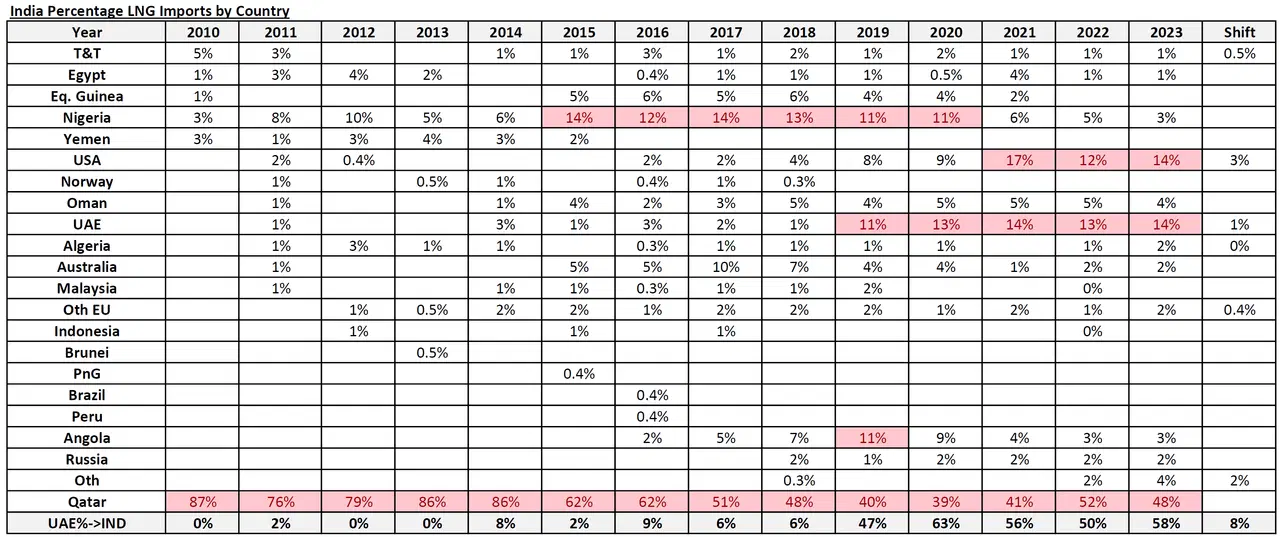

Qatar remains India’s largest supplier of LNG, the United Arab Emirates (UAE) is second, and the United States (US) is a close third. Together, they constitute nearly 80 per cent of our gas imports. Offtakes were slightly up from all three nations in 2023.

India had commenced a weaning-off from Qatar, but the pandemic and then the trade disruptions and shortages caused by the Russo-Ukrainian conflict restricted our efforts at diversification of sources.

Serious, regular American LNG exports to India (and China) first began during the presidency of Donald Trump. The move was a creative way of reducing America’s trade deficit with both nations, and, concomitantly, of using that increase in domestic exploration and production activity to boost the American economy.

It worked for a while, but policy myopia under President Biden, plus a gamble to replace Russia as Europe’s principal energy provider, instead led to a weakening of drilling activity and a resultant inability to satisfactorily serve the market.

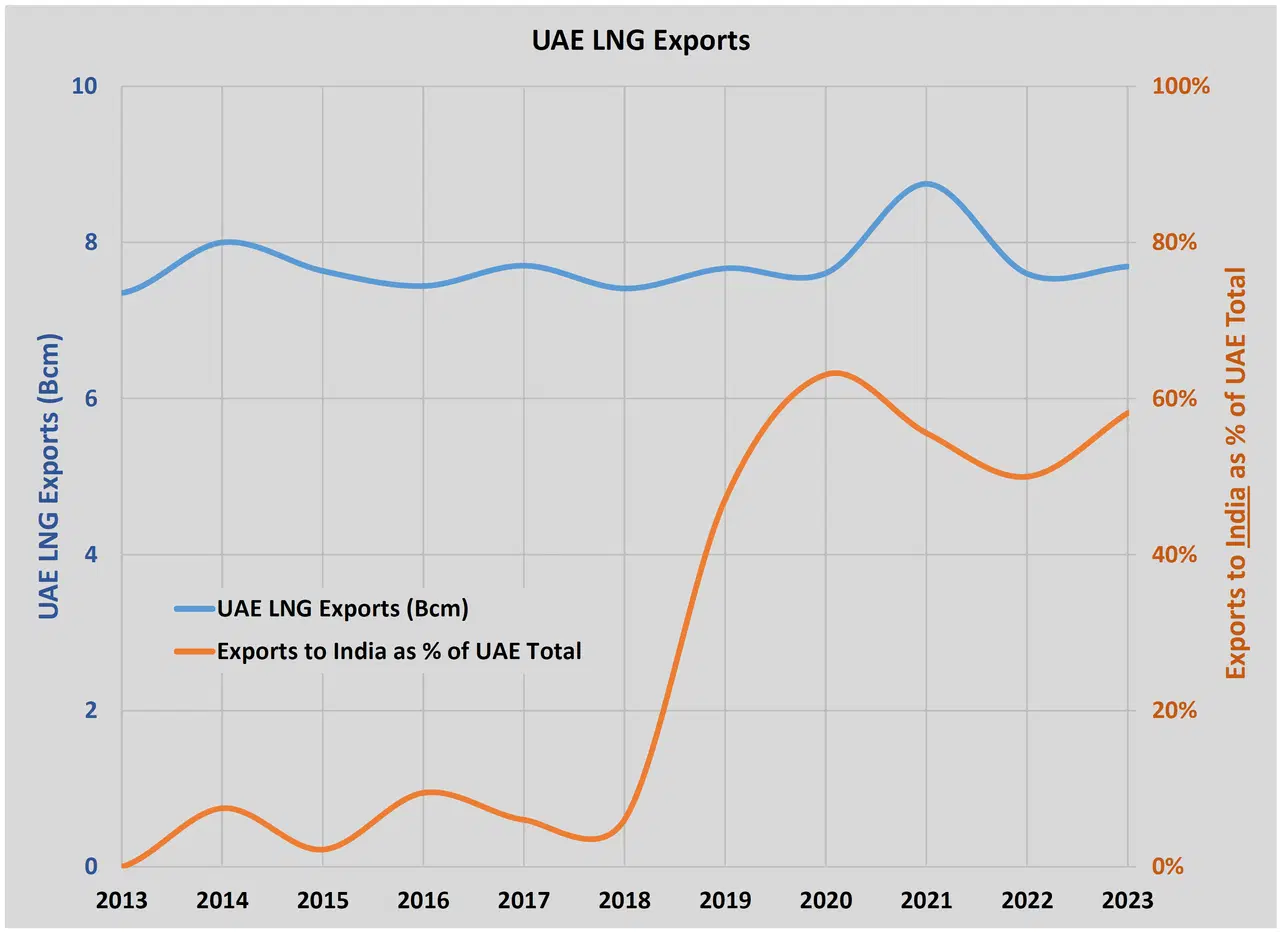

The quiet winner has, however, been the UAE. While its overall LNG sales have stayed stuck at around 8 bcm per annum, the volumes it sold to India started rising quite steeply from 2018; and today, 60 per cent of Emirati LNG goes to India.

That is a very significant figure because sellers, like buyers, don’t normally like to put their eggs in one basket. There are reasons for this.

LNG is a difficult market to break into because of the scale of investments involved. There is simply too much at stake; any disruption in a project’s revenue stream will affect its economics, since the market is not growing so fast that it can accommodate volumes available for offtake.

LNG is still very much a buyer’s market, and made more so following Europe’s senseless, counterproductive ostracism of Russian piped gas since 2022. Consequently, every spot purchase from a buyer nation is a cause for heady celebration, and long-term deals are so assiduously sought-after by exporting nations that they are willing to compromise on a lot else.

In this scenario, the deal between the UAE and India offers the Emirates an excellent opportunity to consolidate its existing production while preparing for expansion both domestically and in foreign projects.

A good example is the recent announcement of a joint venture involving the Abu Dhabi national petroleum company and a Chinese one to develop a giant gas field complex offshore in Mozambique.

And if readers are puzzled over why the UAE, with such large gas reserves of its own, wants to invest in southern Africa, that too in deep waters where the production costs and risks are so much more, welcome to the arcane, rabbit-holed world of the oil patch where nothing is what it seems.

On the other side of the table are those who have lost market share. Africa has been selling less LNG to India with each passing year. By 2018 and 2019, India was buying a third of its LNG from this continent, but in 2023, that figure has dropped to under 10 per cent.

Even more affected is Australia, which declined from 10 per cent of Indian LNG imports in 2017 to just over 1 solitary per cent in 2023.

To make matters worse, Australia is, along with Qatar, now losing global market share to America. And its biggest market, China, bought less Australian LNG than the year before for the third straight year in a row. That is how competitive the LNG market is.

Poor, poor, Australia: the more stories they publish about allegedly nefarious Indian espionage activities, or the more they remain a cat’s paw for other forces, the lower their chances of getting a decent slice of the Indian LNG pie (or the Chinese one for that matter).

In time, nations like Australia will have to make the hard choice on whether to pursue their own interests or that of others at the cost of their own.

As it is, Russia and Iran are preparing to storm the LNG market in a few short years. Then, there are the mega LNG projects in Tanzania and Mozambique that should be operational by the end of this decade. India has a keen interest in the first and is heavily invested in the latter.

And on top of it all is the stalled LNG plant in Yemen, which ceased operations in 2015 because of the civil war there. But wars end.

That is a lot of LNG set to make it to the market this decade, and the bulk of it is in the Indian Ocean region. What will leading exporters like America, Australia, and Qatar do then?

The American Ambassador to India, Eric Garcetti, who suggested recently that India ought to take America’s side in the latter’s conflicts, would do well to bear that in mind, plus the fact that Texan oilmen carry more clout than his patronising pontifications.

Put together, it heralds an exciting era for Indian diplomacy as we ensure our energy security at the right cost to fuel our industrial boom.