Ever since the Indian Prime Minister has announced the GDP target $5 trillion by 2024-2025, there has skepticism whether the nearly $3 trillion Indian economy is growing fast enough to reach the goal. The green shoots that were visible have been met with global headwinds of US-China trade wars and the recent outbreak of Coronavirus (COVID-19) which has sunk markets across the world.

In order to reach its GDP goal of $5 trillion, India’s economy will need to grow at a sustained rate of 9% over the next five years. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) this January 2020 revised downward India’s growth forecast by 130 basis points to 4.8% for 2019- 2020. In its World Economic Outlook update said that growth in India slowed sharply “owing to stress in the non-bank financial sector and weak rural income growth.” The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), has trimmed India’s GDP forecast by 110 basis points to 5.1% for 2019-20 due to COVID -19.

Does Growth Rate Matters?

Are we obsessed with the GDP numbers, or should we also look at other economic datasets? The first is the pace of private and public investment, particularly investment in terms of actual capital expenditure and capital formation. The second is the pace of growth in new income and job opportunities, such as the employment created by sectors that are usually captured e.g. e-commerce platforms in food delivery, taxi-hailing, etc. The third is the growth in per capita income.

Liquidity has been the major challenge which India is facing due to which there has been limited credit offtake, The strain in the banking sector is more of structural than cyclical, the crony capitalism that thrived during the 2004-2014 period has crippled the banking sector, a few non-banking finance companies had “some deep-rooted issues” because they engaged in corrupt practices and fraud. The lack of oversight is visible even today and now the chickens are coming how to roost.

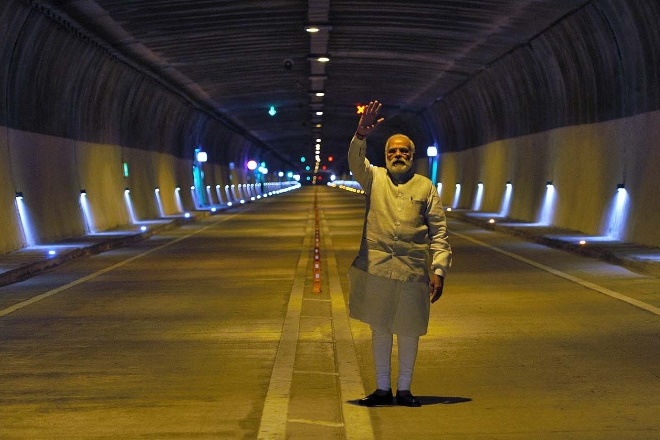

The Indian government is trying to make financing available for infrastructure projects. One is the creation of the National Investment and Infrastructure Fund with investors such as the Abu Dhabi Investment Authority, Temasek of Singapore and the HDFC Group. The government has also announced Rs. 100 trillion ($1.4 trillion) in infrastructure projects covering the power, railways, urban irrigation, mobility, education, and health sectors. Efforts to sell stressed assets of India’s public sector banks and divest government holdings in state-owned corporations are other encouraging signs. In the latest Union Budget that was presented, the government set a disinvestment target of $2.1 trillion by 2021.

Attracting Investment for Infrastructure

It took India 60 years to get to the first trillion dollars, The next trillion took 10 years and then from $2 trillion to $2.9 trillion took roughly three years. Now, in five years to do $2 trillion is achievable. The sine qua non is attracting investment in the Infrastructure sector – the decade between 2005 and 2015 saw almost a trillion dollars of investments in infrastructure projects in the country. The second trillion can be achieved if we do the right things.

Over the next few years, the four largest global metro footprints will include three in China and in India the fourth will be in Tokyo, edging out London and New York City. If India can attract directional investment in infrastructure, the road to $5 trillion GDP is within striking distance.

Legacy of PPP misuse

Rampant abuse of the public-private partnership (PPP) model in the past decade was the reason why global money was shying away. In India, PPPs became TTTs, or taxpayer-to-tycoon transfers, an infrastructure project would be gold- plated with inflated costs that banks would fund, enabling private sector participants to take out their equity even before commercialization.

The private sector partner would stick to the project only if it was generating positive cash flows. On the contrary, if it was non-profitable these partners would walk away with banks left holding the toxic loans in their books. Many of those PPP abuses occurred between 2006 and 2012, saddling public sector banks with nonperforming assets the tremors are being felt even now. Since the government is reluctant to let public sector banks go under, it recapitalizes them with taxpayer money.

Need for PPP 2.0

It is imperative that the PPP model re-emerges in a different way. One of the alternatives and sustainable ways to operate infrastructure projects is to build them using government money, and once it’s a cash flow yielding asset, hand them over to the private sector to operate them. Mumbai and New Delhi airports are prime examples of private sector companies taking over operations after they were built with public funds.

Cash-flow Vs. Under-Construction dilemma

Global investors are attracted to cash-flow generating assets like existing airports to operate and leverage them to invest in greenfield projects. Recently, Government has increased oversight by monitoring the National Infrastructure Pipeline (NIP), improved transparency in the governance of projects, auction systems for allocation of licensing for public resources, the existence of a top tier of well- managed private companies and other market mechanisms such as the creation of funding platforms for infrastructure, like National Infrastructure Investment Fund (NIIF).

Under-construction projects are not attractive to investors and have underlying risks. Cash flow generating assets look like ‘Butterflies’ are lovely, as they bring in steady cash flow for a long period usually in the next 30 years.”

The upside of these Cash-generating assets is that they will attract /and are attracting international funding mainly because they have secure cash flows in sight. For example, a second terminal at Mumbai’s international airport is a “butterfly”, since it is built by private sector partner GVK Power and Infrastructure, but the same company’s winning bid to build a greenfield airport in Navi Mumbai will find it challenging to attract international capital, as it carries more due to under-construction category.

Cash-generating assets are more in demand, as recent deals show. Last October, NIIF and its partners Abu Dhabi Investment Authority and Canada’s PSP Investments signed a deal to acquire an equity stake of 26.3% each in the GVK group’s holding company that owns Mumbai international airport, for a total value of $1 billion.

It is imperative the government should open cash-generating opportunities for investors in assets with existing cash flows such as railway stations. With an assured footfall of at least 300,000 in a railway station it can be a cash cow for any private operator.

Similarly, a flurry of activities in urban transportation space is been seen where many Indian cities planning to build their own metros, and that in the next 10 years, at least 25 Indian cities will have state-of-the-art metro systems.

So, rounding up, the $ 5 trillion target looks achievable if the infrastructure is kept at the core of the strategy for the government. Corollary to this will be the flow of international capital into cash-generating assets and competitiveness of the country matched by strong political will supported by strong financial institutions like Development Financial Institutions (DFI’s), other enabling institutions.