A ground report dives deep into what the residents of Asia’s largest slum think about the plans to transform it.

Mumbai, as the bustling financial nucleus of India, is undergoing a profound metamorphosis, characterised by a burgeoning infrastructure and a rapidly evolving real estate sector. However, alongside its prosperity, the city also harbours the most densely populated slum settlements, where many of the low-income groups find homes, owing to the expensive housing market.

Over the years, the redevelopment of such slum settlements, has also been a major constituent in revamping the city and its populations.

On similar lines, Dharavi, Asia’s largest slum, sprawling over 259 hectares and accommodating approximately 600,000 residents and 12,000 commercial establishments, has been presently the focal point in the series of redevelopment projects in the city.

Initially proposed in 2004, the project has always faced political complexities and opposition.

However, overcoming these hurdles, it has advanced to its next phase, as the Maharashtra government granted approval to the Adani Group to transform the settlements which lie in the heart of the city.

But unlike other slum redevelopment initiatives, what stands different is that this will rather be a redevelopment of ‘an informal city’ that has emerged within Mumbai, with many residents and commercial activities deeply ingrained in the existing settlement for years.

What’s Life Like In Dharavi

“Dharavi is not just where we live, but it is the place where we have built our livelihoods for the past 100 years,” says Dinesh Rathore, a potter from Kumbharwada, one of Dharavi’s earliest settlements, where he lives with his wife, three kids.

“We have been doing this generationally, our ancestors were the first to move here. All of this neighbourhood is packed with potters. Our shelters, workshops, and markets are all in this small area,” he told the reporter.

The main road of Kumbharwada can be seen with shops selling clay pots and ceramics.

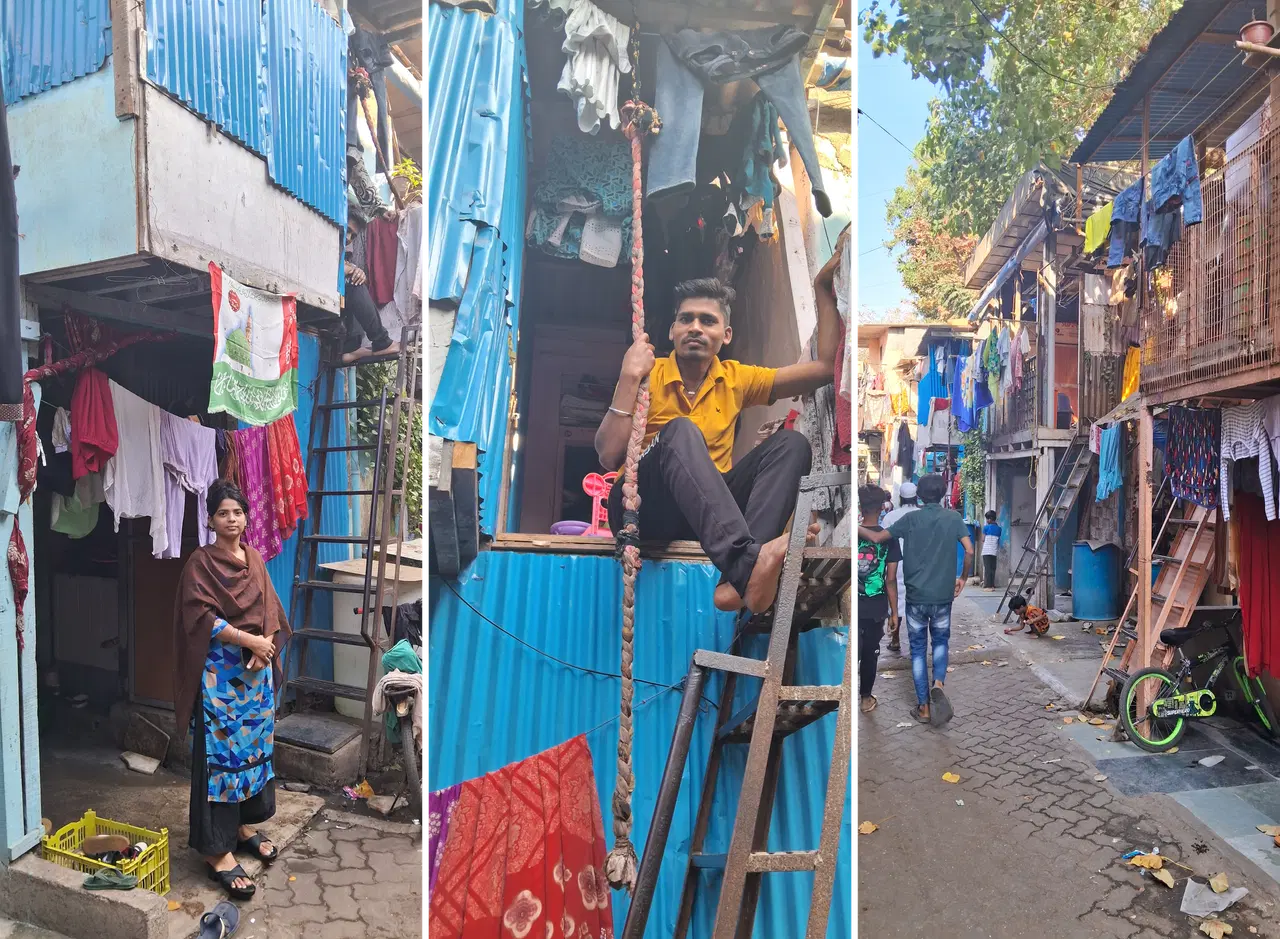

As one goes inside the narrow lanes, bordered by open drains and tangled wires on the top, the area opens up to clusters of small huts and clay furnaces, with billowing smoke andJYA relative quietness enveloping the area, starkly different from what was visible on the outer street just a few metres away.

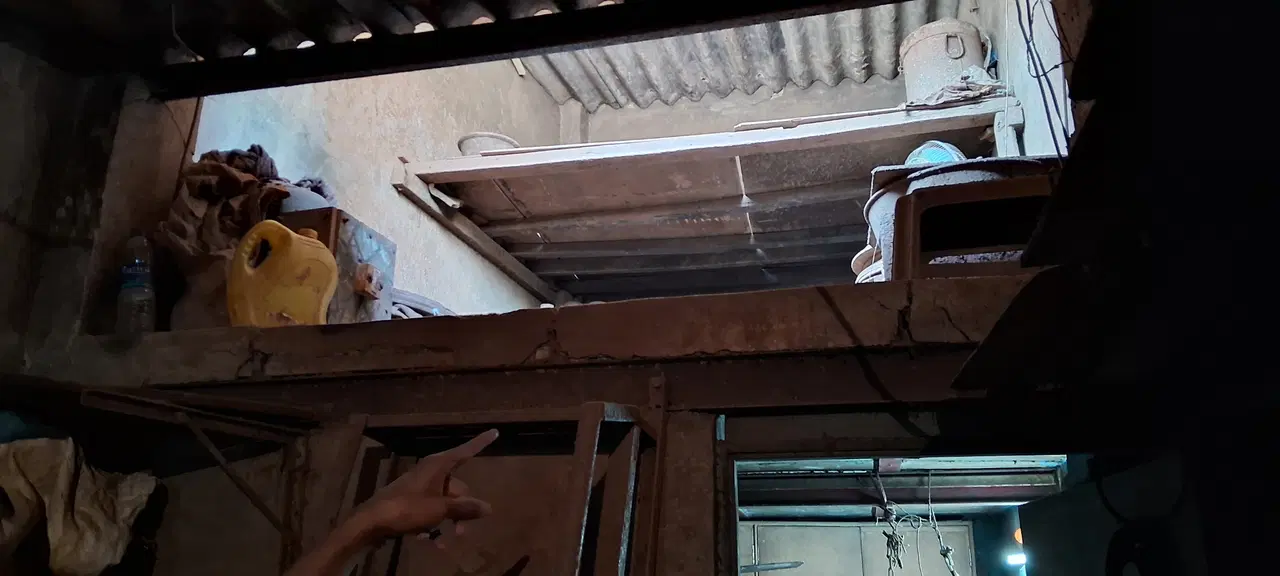

Among these, Dinesh resides in a 10 ft by 18 ft dwelling. The ground floor serves as living space for his family, while makeshift floors above are for his pottery workshop.

He said, “Everything has to be managed here according to days. Me and my wife have to start at 6 am, prepare the clay, and keep it aside to make space for other activities throughout the day.”

Pointing to a nearly vertical metal staircase leading upward, he shows the layers of mezzanines created with just enough space for one person to move around in a bent posture, where he makes the clay pots and keeps its for drying.

Outside this tiny hut, a 10 ft-by-10 ft kiln is used for baking the pots. This is a common sight behind every house in Kumbharwada, that has also shaped the layout of the narrow lanes.

“Over the years, all houses here have learned to utilise available space similarly,” he added.

Kumbharwada traces its roots back to the late 1800s when groups of potters migrated from Saurashtra and Kutch in Gujarat. Since then, the community has been in Dharavi, sustaining itself through the craft of hand-spinning pottery.

Despite being a traditional industry, the working conditions appear to be extremely confined and hazardous. The smoke emanating from the furnaces fills the entire surroundings throughout the day, making it nothing less harmful than an industrial chamber.

While Ranjit does not feel the difference, his wife, says, “With no space around, there is no escape for the smoke, and it seeps into our homes. Over the years, the materials used are also contaminated with unknown elements, which has now started bothering, especially the kids who are playing in the same smoke.”

“Mostly all here have always welcomed the proposal for redevelopment. Look at the conditions around now, there is no other way for us to improve our working and living conditions this way,” she added.

“Although nobody has approached us yet, we are seeing the news about the survey that is about to start. They should begin the work, and also meet us to do something for our betterment.”

A group of residents added, “They will give a house which is 350 square feet in size. That is for living. But the space will not be enough for our work. We need a place to set up our shops and work safely. The government urges us to continue and keep alive this craft. Our generations can only take this forward with better working conditions and their support.”

“Having a fixed-size home is acceptable. It will only stop these illegal expansions, where people are being squeezed into cramped spaces. This development will also push people to move out and do something for themselves, rather than just sitting here and occupying informally.”

Alongside the potters, leather tanners from Tamil Nadu, embroidery workers from Uttar Pradesh, and a rapid influx of migrant labourers from across the country have established their presence in Dharavi, leading to continuous expansion and densification of the settlement.

Most shanties double as workplaces for many small-scale industries, built with metal sheets, waste plywood, and plastic.

These hutments, layering up internally, has multiple business ongoing, which has made Dharavi not just for shelter, but also into a micro-economy with many unorganised industries including pottery, leather tanning, plastic recycling, garment manufacturing, and packaging.

More than 60 per cent of the city’s plastic waste is recycled within the cramped industrial spaces of Dharavi.

Even people, who only live in Dharavi, but work in other parts of the city, have expanded their nearly 10 ft x 8 ft shanties by adding another room on top, which they rent out.

Many neighbourhoods are dominated by these tiny rented rooms, multiplied across streets and mostly inhabited by migrant labourers.

Sakira owns one such hutment near the plastic recycling industries, where she finds odd jobs, while her husband works as a taxi driver.

While she wishes for changes, she worries about the uncertain future, feeling like a small piece of a massive puzzle.

She says, “We do not know where they will move us. Our lives have been here but look at our living conditions. I have two kids, my husband and his mother, we all have to fit in in this dabba (calling her hut a box out of frustration). The kids have to use public toilets, paying Rs 3-5 each time. We have been waiting for years for redevelopment, but nothing has happened.”

Adding to the plight are also the very few public toilets — only 1000 toilets for 1 million residents, according to reports.

“We would prefer to stay in this area. Huts are all the same, but there is at least some space for the kids to play, and I can find work in the nearby industries.”

In most huts, the owner occupies the lower level while the first floor is for migrant labourers, with six, some places even eight, crammed into a single tiny room.

“We don’t know what will happen to the tenants and others living on the first floor,” says Jeenat, who owns a hut and has rented out the mezzanine space.

With numerous challenges evident, it is clear that the Dharavi redevelopment project is not just about relocating people to new homes but also an opportunity to transform entire livelihoods by improving the industrial and working conditions of the people.

As many look forward to the changes, the current socio-economic constraints rooted in Dharavi call for a careful approach from both the government and developers, considering the population diversity and their connections to the area.

According to the Slum Rehabilitation Authority (SRA) rules, those residing in Dharavi on or before 2000 are eligible for a 350-square-foot dwelling within the redevelopment project.

Additionally, considering the industrial micro-economy of the settlement, commercial spaces of 225 square feet will be provided free, while areas beyond that, will be available on payment of the construction cost.

However, the eligibility criteria were based on a survey conducted in 2008. Since then, the population has doubled.

The 2008 survey covered approximately 56,000 structures, while, nearly two decades later, it is estimated to cross over a lakh structures, with several layers of usage.

For the same, the government is doing a new survey to get an exact count of the eligible residents, which is expected to begin this month.

SVR Srinivas, CEO, Dharavi Redevelopment Project, said, “Usually we only have to deal with 300–400 people, but this is a large-scale project. The ineligible don’t get anything, but Dharavi is a special project, so those who are eligible will get free houses, and those who aren’t eligible will be accommodated in a rental housing project.”

For those who moved between 2000 and 2011, a 300-square-foot dwelling will be provided outside Dharavi, within the Mumbai Metropolitan Region (MMR), with a payment of Rs 2.5 lakh under the PM Awas Yojana.

While for those who have been living post-2011, there is no provision in the SRA.

However, for Dharavi, a special provision has been made to rehabilitate the residents on land which will be provided by the government, providing homes on rent or for a higher purchase (rent to be treated as instalment for the home value).

Based on the survey, each eligible household will be a beneficiary of one home, and the same with the case of working spaces.

Architect Hafeez Contractor, design firm Sasaki, and consultancy firm Buro Happold are those given charge of the ambitious project.

As per the Adani group, the master plan has prioritised social infrastructure, including hospitals, public spaces, and skilling centres, which are lacking in the region but essential given the large population.

To begin the rehabilitation work after the survey, officials say, that the 47 acres of railway land acquired will have the first set of construction. Since the extra piece of land will give the much-required breathing space, there will be no need for temporary rehabilitation, and the first phase of permanent rehabilitation will be on the railway land.

Dharavi retains a prime location in Mumbai with proximity to existing business districts and financial centres of the city, including the Bandra Kurla Complex (BKC) and Nariman Point.

Aligning this with Mumbai’s changing landscape, and considering the current livelihoods and informal micro-industries, the plan incorporates industrial and business zones to support both existing and new businesses.

These zones will offer enhanced infrastructure, and platforms for improved conditions and growth while addressing the current haphazard conditions that exist presently.

Bringing together regulations within Dharavi’s industries will provide opportunities for formal market access. Presently, artisans and other workers often rely on intermediaries, prone to exploitation. Formalisation and decent workplaces will enable them to engage directly with potential customers.

For years, Dharavi’s position as a complex maze has deterred many from venturing into its congested spaces, leading to a sense of isolation from the rest of the city.

As the project takes steps, it will continue to face inevitable challenges, but its revamped identity will aim to reduce this differentiation and open up this massive area for integrating with Mumbai’s progressive landscape.