- The pity is that the geological dangers were known to everyone for ages, and yet, nothing was done by successive state governments to mitigate risks.

Kerala suffered its worst natural disaster on 30 July when two landslides in the Meppadi panchayat of Wayanad district, at the southern end of the Western Ghats, hit the villages of Mundakkai and Chooralmala. The devastation was terrible. Hundreds died, and hundreds more are missing.

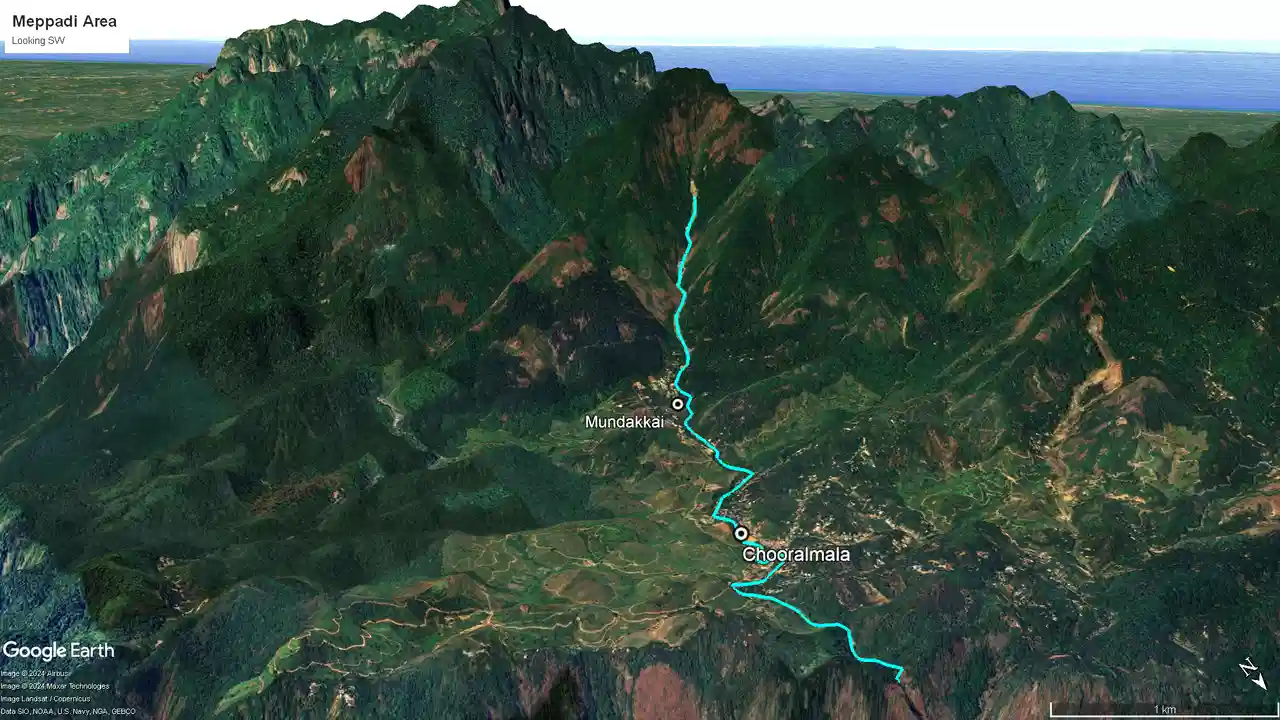

Both villages lie on the Iruvazhinji River. Its catchment area is a circular cluster of steep, jagged ridges that crest at the 2,350-metre-high Vavul Mala peak. As the map below shows, the two villages lie in a basin, precisely on the route that funnels torrential downpours during the monsoon downstream to the Soochipara waterfalls.

Consequently, Meppadi panchayat has for long been identified as being highly prone to flash floods and landslides. In technical terms, such incidents are called rapid mass wasting. The problem is exacerbated here because of the boulders in the river bed.

Mere water during a flash flood, for example, has insufficient capacity to shift these boulders over long distances, but when there is a landslip along with heavy rains, the mud, water, and air combine to form a high-velocity slurry that can do so. Then, these boulders transform into deadly buoyant projectiles, which are transported for kilometres along trajectories that cut across a river’s traditional, lazy meanders.

In Meppadi panchayat, the rapidity of such movement is enhanced by the added force of gravity because of the steepness of the Iruvazhinji River’s gradient; it drops from an elevation of around 1,800 metres to 800 metres in just seven kilometres. Add the water and silt brought into the Iruvazhinji by other tributaries upstream of the disaster sites, and one may gauge the tremendous fury that hit the two villages.

The 3D satellite map below shows the locations of the buildings in Mundakkai village. Note how they cluster at the valley floor, right in the path of everything nature hurtled down the slopes that fateful night.

The pity is that these dangers were known to everyone for ages, and yet, nothing was done by successive state governments to mitigate risks. In 2009, the National Centre for Earth Science Studies (NCESS), headquarters at Thiruvanathapuram, conducted a landslide susceptibility study and prepared a hazard zonation map of the area, which was issued to all district collectors.

In early 2023, the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) issued a landslide atlas that, too, identified the Meppadi area as being particularly prone to landslides. The Union Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) issued multiple warnings to the government of Kerala in the week preceding the disaster, as did the Indian Meteorological Department, the Central Water Commission, and the Geographical Survey of India.

And tragically, the Hume Centre for Ecology and Wildlife Biology located in Kalpetta town, Wayanad, which has a dense grid of rain gauges in the area, issued a warning exactly one day before disaster struck.

Therefore, one can’t blame this disaster on climate change (as some have tried), because that is not how science works. It is basic geology that every once in a while, sedimentary accumulations on slopes will erode abruptly for multiple reasons, triggering landslides, flash floods, shifts in river courses, and destruction.

So, Bhupendra Yadav, Union Minister of Environment, Forest, and Climate Change, was spot on when he said that the incumbent Pinarayi Vijayan government laid the ground for the disaster by ‘aiding and abetting illegal mining and habitation’ in an ecologically fragile district like Wayanad.

In the case of Mundakkai and Chooralmala villages, the key word is habitation. If only the houses had been built slightly further away from the river banks, and at 10 metres higher elevation, hundreds of lives would have been spared. The onus should have been on technocrats and bureaucrats in the first instance, and on the political class secondly, to ensure a bare minimum respect for such potential furies while making policies.

Unfortunately, this is an idealistic, even a utopian thought, because that is not how things work in God’s own country. In a densely populated state like Kerala, where the bureaucracy and “civil society” are so intensely politicised, and so in tune with the political classes on the issue of land, what can district magistrates do? Their hands are tied in five different ways.

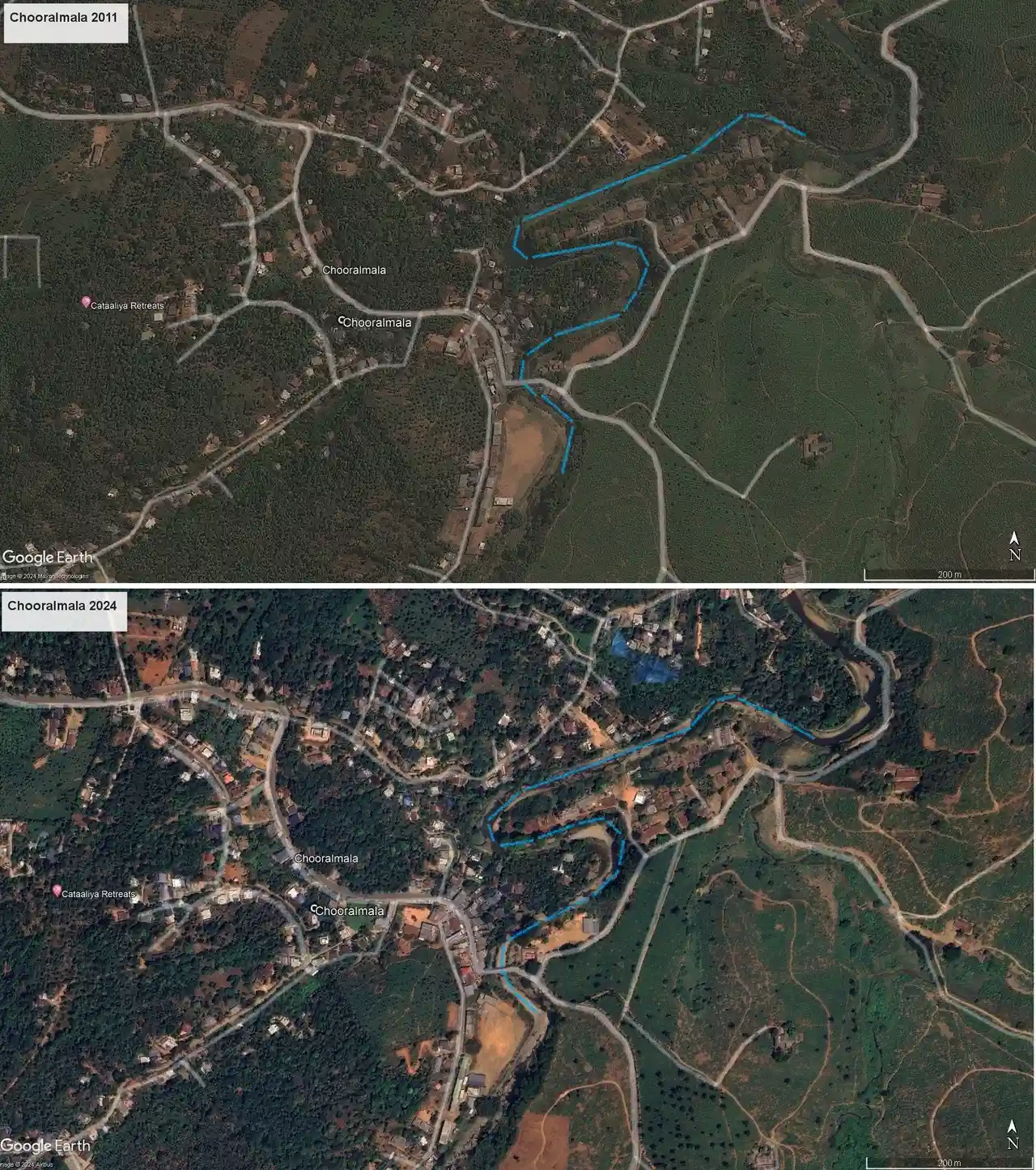

For proof, compare the land use patterns of Chooralmala village at the valley floor between 2011 and 2024. The Iruvazhinji River’s course is marked in blue. Note the number of new constructions that came up along the river banks during this period.

It is the other social contract no one talks about, between selected and elected officials on the one hand and the public on the other, whereby such risks are quietly sacrificed by tacit mutual consent at the twin altar of pressure on land and profit. What, then, is the point in bringing up the NCESS map? Or the ISRO map?

To that end, the central government’s decision to reissue a draft notification (for the sixth time in a decade) classifying parts of the Western Ghats as ecologically sensitive areas is a welcome first step since it would impose a ban on quarrying, sand mining, and large-scale infrastructure development. But it is both inadequate and doomed to fail because the decision in such cases rests with the states.

Thus, until the Kerala government institutes a comprehensive rehabilitation programme, at least in high-risk areas like Meppadi for a start, the sad truth is that tragedies like the one that struck there on 30 July could happen again. This is the problem with being bankrupt and still chanting the federalism mantra; try eating the cake and having it too, simultaneously, and it will be nature that does the eating in the end.