Muniya Devi lives in one of the first houses as you enter Miya Bigha ward in Bodh Gaya — a revered town renowned as the birthplace of Buddhism.

Located just 500 m away from the Mahabodhi temple — a UNESCO-designated world heritage site, her house and the ward come under the core area of the town, but are discreetly nestled behind the busy road and commercial establishments, making them inconspicuous to the town’s many visitors.

Bodh Gaya holds profound religious importance globally as the site where Gautama Buddha attained enlightenment.

Flanked by the Falgu River to the east, it is home to numerous sacred sites and serves as a hub for spiritual practice, attracting thousands of monks who serenely impart Buddha’s teachings.

While Bodh Gaya’s facade greets a considerable influx of visitors with a thriving tourism industry, the region of Bihar is infamous for its water scarcity issues, a concern overshadowed by the its tourism.

Each day, Muniya Devi confronts the daunting task of securing water for her six-member household. Her house stands out in the ward, as it has access to a water supply pipeline that operates twice daily, providing water for just half to an hour on each occasion.

A short window, in which, not just her, but around 20 neighbouring households must fetch enough water from the same pipe to last the day.

When questioned about the water situation in the area, especially regarding the “Har Ganga Jal” Scheme, launched in November of the previous year, Muniya Devi vents her frustration.

She points to the common pipe situated perilously close to a gutter, explaining that this pipe was installed years ago by the Public Health Engineering Department (PHED). She tells Swarajya that it is the only source of water shared among the neighbourhood every day.

Further, she indicates a network of blue pipes scattered throughout the area, which lies defunct.

This network, locally termed as the “Blue Balti” piping, was supposed to provide piped water to approximately 6,000 houses in Bodh Gaya, as per official records, yet it remains non-functional.

Walking around the ward reveals a diverse array of households and guesthouses. While some residents cannot afford private groundwater solutions, others have resorted to borewell systems to address their water woes.

Narendra Prasad, a retired official of the PHED also has his house in the same ward, who after losing all hopes from the government’s water supply pipelines, that never reached their street, has opted to rely on ground water.

He further shows around the neighbourhood, and points to a similar common pipe as Muniya Devi’s, where smaller households come to collect water for their daily needs.

He adds, “For many in the area, this common pipe is their sole source of water, and when it runs dry, the people have to depend on the support of the neighbouring houses to lend water for survival.”

This is how the locals of Bodh Gaya, both in this and several other urban wards, have been coping with their daily water requirements, irrespective of caste, social standing, or economic circumstances.

Such remains the state of affairs in this town, even in the wake of the implementation of Chief Minister Nitish Kumar’s ambitious “Har Ghar Ganga Jal” Scheme, which is nearing its one-year completion.

Bodh Gaya’s Water Infrastructure and Crisis

The water shortage is well-recognised in Bodh Gaya among its residents and officials. In order to gain a wider understanding of the factors contributing to the present water situation, it is imperative to delve into the water infrastructure conditions that have been in place over the years.

Bodh Gaya, is located 15 km from Gaya town, with a population of around 72,000. It was designated as Nagar Parishad (City Council) in 2021. The area heavily relies on groundwater, despite being a dry region for most summer months.

As a well-known tourist destination, the town’s expansion has resulted in depletion of subterranean reserves, and water quality issues.

A Bihar PHED investigation revealed a substantial decline in the average groundwater level in Gaya district, from 30.30 feet in July 2021 to 41.50 feet, in July 2022.

Recognising Bodh Gaya’s cultural and religious importance, it was chosen for the Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission (JNNURM) in 2006.

Under this, to improve the water conditions of the arid town, pipelines were installed, mainly serving the core area around the Mahabodhi Temple, benefiting around 1,200-1,300 households. This supply was managed by the PHED.

Muniya Devi’s house and the whole of Miya Bigha ward is also part of the same piping network.

Further, a public-private partnership water supply project was launched in 2011, led by the Bihar Urban Infrastructure Development Corporation (BUIDCO) and Jindal Water Infrastructure Limited (JWIL), designed to meet the drinking water requirements of 19 designated wards within the then Bodh Gaya Nagar Panchayat (BGNP).

By 2017, JWIL reported the successful completion of its pipeline installation. However, the project was marred by significant issues as many households complained that the company had left pipes outdoors, lacking taps and meters.

With such execution failures, the region continued to grapple with water challenges, with over-extraction of groundwater and relying on water tankers from nearby districts to cope with the hot, dry season.

Bihar Chief Minister’s ambitious ‘Har Ghar Ganga Jal’ Scheme Aims To Address This Ongoing Water Crisis

The ‘Har Ghar Gangajal’ scheme was inaugurated by Chief Minister Nitish Kumar in Rajgir, Nalanda, on 27 November, 2022.

According to Nitish Kumar, the scheme pledges to provide 135 litres of treated Ganga water daily to 7.5 lakh families in regions of Bodh Gaya, Gaya and Rajgir —to overcome the challenges of water shortages and excessive groundwater extraction.

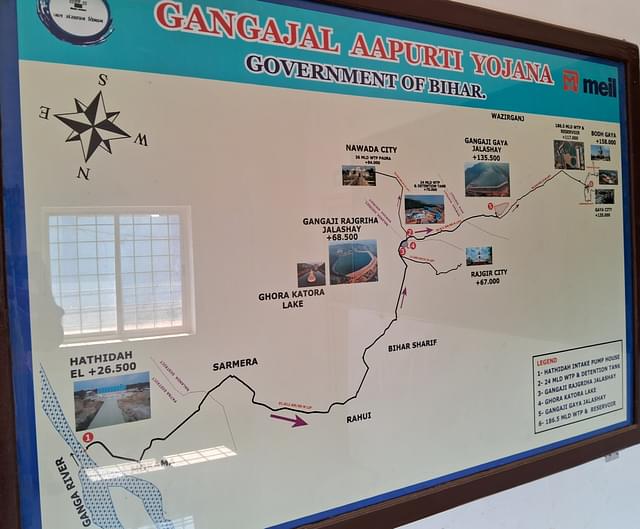

Hyderabad-based Megha Engineering and Infrastructures Limited (MEIL) took charge for implementing this pioneering project. The project aims to harvest Ganga water during monsoon floods, which will further be treated, stored, and piped to these regions.

Costing nearly Rs 4,000 crore, the project will transport lifted water across a distance of 150 kilometres from Hathidah near Mokama to these households using both existing and new connections.

According to Bodh Gaya Nagar Parishad official, 20 per cent of the lifted water goes to Rajgir, while the 80 per cent reaches to supply for Gaya and Bodh Gaya.

For its supply to Bodh Gaya and Gaya, MEIL has constructed pump houses and storage reservoirs at Tetar and Manpur (Gaya) of capacity 18.633 million cubic metres and 0.938 million cubic metres, respectively.

The Manpur plant daily supplies water to underground reservoirs (UGR) for Bodh Gaya and Gaya. During Swarajya’s visit to the WTP plant, MEIL officials explained the overall process, starting from storage, to the multiple steps for treatment, before the water is released to the towns.

The officials also confirmed that close to 20-22 MLD of the total daily water quantity of 55 MLD, is released for Bodh Gaya, which is sufficient to fill the UGRs for Bodh Gaya.

Beyond MEIL’s effective role of lifting water and reaching it to the reservoirs of Bodh Gaya, the essential task of water distribution falls under the state authorities, who are responsible to ensure piped water supply to the houses.

Upon the launch of the scheme, the Chief Minister stated, “There is no need to depend on groundwater now. Do not extract it. It is the reason behind many problems.”

However, the practical aspect of water distribution under the ‘Har Ghar Ganga Jal’, which claims to ensure that water reaches the 6,000 households in Bodh Gaya, unfolds as a different narrative on the ground.

One Year Of ‘Har Ghar Ganga Jal’ Scheme In Bodh Gaya

Coming back to grasp the real situation concerning this state government’s scheme, Swarajya conducted visits to several of the 19 wards — as this initiative relies on the same water supply network which was meant to serve all households in these urban areas.

For a broader coverage, Bodh Gaya’s landscape can be divided into several zones. The area surrounding the Mahabodhi Temple signifies the older, central settlement. As it expanded, neighbourhoods in the north along the Falgu River grew, which also has the Nagar Parishad’s office and water pumping facilities.

Additionally, there has been rapid development towards the west, along the Gaya-Dobhi Road which now accommodates several commercial establishments and well-known institutions such as IIM Bodh Gaya and Magadh University.

Each ward reveals a unique water story — where the locals either face issues like no direct connections, struggles with shared older connections, or continue to rely on groundwater, if they can afford it.

Bapu Nagar, claimed to be the largest ward in Bodh Gaya, has a population of around 5,000 and is situated in south-western part of the town.

Despite rapid growth in the last five years and the presence of institutions like IIM Bodh Gaya, Magadh University, IHM Bodh Gaya, and several other monasteries and tourist places — the water supply situation remains stagnant.

The pipes in these regions are still non-functional and abandoned on the roads, forcing most houses to rely on groundwater.

When asked about using groundwater despite the government’s Ganga Jal scheme which theoretically eliminates the need for groundwater reliance, Kanti Devi, residing in one of the larger houses in the settlement, explained that the Ganga water could not reach their homes as the pipes were never connected to any of the houses.

She said, “What is the other way of getting water? The pipeline lay broken and damaged over the years due to lack of maintenance.”

“I have to meet the water needs of my family of seven and support my laundry and ironing work, so I have installed a borewell system, incurring regular maintenance costs of about five to six thousand rupees every six months, in addition to electricity expenses.”

During the summer season, when groundwater levels drop, they have to dig deeper to access water.

She expressed her wish for the government to repair the pipelines and provide water through the scheme, which could benefit all the houses without any water supply.

Further, she showed a pipe outside her house which she has placed for the benefit of other members of the settlement who lack alternative water sources.

She explained, “Many families in the surroundings cannot afford groundwater and depend on this pipe for daily water needs. I keep it running for some extra time after our water tank is filled.”

While this represents the situation in wards where pipes never reached homes, there are a few settlements near the town’s core that were fortunate enough to have functional pipelines supplying water to their houses.

However, most residents are unaware of the Ganga Jal Scheme’s initiation, as they report no change in their water supply since the scheme’s inception.

Tracing the settlements where water supply through this scheme is active, one such area is Pachati, a ward located near the Mahabodhi temple and the Kalchakra maidan, where a positive application of the piping network can be observed.

Arshad Ansari, who runs a convenience store, lives in a two-storey family house with three brothers and families.

He says, “We had received four pipelines in all our names. However, one of the pipes did not function, the remaining three connections have been connected to the water tanks since the piping has come in place.”

On the borewell systems, Arshad mentioned that they had such setups earlier. However, they removed it after the piped water supply was established, nearly four years ago, as they were no longer required.

Most of the houses in the surrounding, all close to two-storeyed, have transitioned to using the piped water supply. Although, they are unaware that the Ganga Jal Scheme has begun, and are receiving water lifted from the river, as they say that there has been no change or improvement in the water supply ever since.

While others in the same settlement, have a different opinion about the piped water, and continue to use the ground water systems, one family stated, “We do not know about Ganga Jal, but this water supply definitely gave us Ganda Jal (Polluted water).”

In areas near the Falgu River, the same water supply challenge persists due to the absence of direct connections to houses, leading residents to continue depending on groundwater systems.

Chunnu Kumar, a resident of Amwan Ward, receives water from the pipe network, but his family still relies on the groundwater system they had in place. Due to unreliable supply, they keep the piped water as supplementary for smaller purposes whenever it becomes available.

For many homes in these settlements, piped water, voluntarily pulled inside their homes, serves as supplementary supply, rather than the primary source.

However, in houses lacking a groundwater source, this piped water has become their lifeline. Groups of residents can be seen using a common pipe to collect water when it is available.

Regarding the recent scheme, they express that they are not overly concerned about Ganga water but require more consistent water supply options, eliminating the need to struggle for water when the supply cuts.

Meanwhile, the irregular supply and lack of proper connections, and meters, has resulted in pipes being left open at many places with water continuously flowing onto the roads and into the drains.

Vijay Kumar, councillor of the ward, pointed out the open pipes, acknowledging that this is the Ganga’s water going to waste on the roads.

“If authorities can connect this supply to homes and ensure regular delivery, the network could efficiently provide water to all households in his ward,” he says.

Bihar’s Urban Areas Struggling With Messy Execution And Inefficiency

Even as the engineering efforts of MEIL and state government for water lifting aims to replenish dwindling groundwater resources by reducing extraction for supply and improving the overall water supply, the conditions at the end-user level — the local settlements — remains largely unchanged.

The water infrastructure in Bodh Gaya remains precarious, leaving most residents without access to clean water. The sluggish implementation of the distribution system by state authorities has left many continue to struggle daily to secure water resources, even in the face of such large-scale initiatives.

In a region known for water scarcity, the use of groundwater resources persists at the ward levels, with no viable alternatives for residents. This stands in stark contrast to the government’s claims that Ganga water through pipes will reach 6,000 households in Bodh Gaya.

Moreover, the assumed beneficiaries themselves lack awareness of the Ganga water scheme, owing to the inefficient efforts of the state authorities in understanding and resolving the water issues.

Bodh Gaya was granted the status of a Nagar Parishad (city council) as part of amendments to the state’s municipal acts, aiming to expedite Bihar’s laggard urbanisation process.

However, cities like Bodh Gaya, which occupy a central place in the state and nation’s image, are still far from being categorised as truly urbanised, especially when it comes to providing fundamental necessities and amenities to its settlements.

For its water issues, the pressing question remains the same — how will the water reach homes and help people escape water poverty?

In the face of hotels and monasteries, that define the landscape of major roads in Bodh Gaya, there exists a starkly contrary side to the development of the local settlements within this urban area — questioning the development response and the vision of the state authorities.