n 12 October, the first ship docked at the under-construction Vizhinjam International Seaport in Kerala, marking India’s entry into the transhipment club, which so far was missing despite rising trade with the world.

The inaugural ship, a project cargo vessel, Zhen Hua 15 from China, sailing under the flag of Hong Kong, was welcomed at Vizhinjam port in the presence of Chief Minister of Kerala, Pinarayi Vijayan and Karan Adani, CEO Adani Ports.

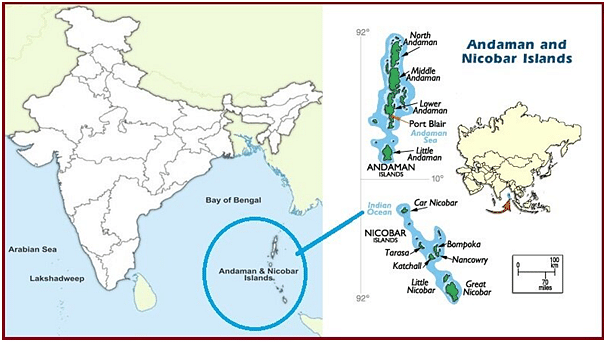

Vizhinjam joins a coveted league of three transhipment ports, currently under implementation in the country, other two being international container transhipment port (ICTP) project at Galathea Bay in the Great Nicobar island and the Cochin port.

Why Transhipment

Transhipment, as the word suggests, is a term used for shipment of goods to an intermediate destination before being shipped to its final destination. It is not restricted only to shipping; transhipment can take place through road, rail and air transport as well.

In shipping parlance, transhipment, is movement of a container or cargo from one vessel (feeder vessel) to another (mainline vessel) while in transit to its final destination.

Major shipping lines have services that cover almost all the ports in the world via connecting ports. These ports are known as transhipment hubs. At transhipment hub port, small feeder vessels bring and pick up containers from large mother vessels (liners), creating economies of scale and lowering the freight cost.

For example, Cotton imports to Bangladesh from central India – Nagpur area moves by rail to Nhava Sheva Port on the west coast of India and is then transhipped via Colombo resulting in longer transit time.

In addition, Bangladesh imports many other manufactured goods from other ports in India such as Nhava Sheva, Mundra, Cochin, Tuticorin and Chennai. All these ports are connected to Chittagong Port through transhipment via Colombo or Singapore, leading to long transit and higher cost for Bangladesh importers, thereby affecting export competitiveness of India.

Also, a lack of transhipment port means India cannot cater to cargo bound for its neighbouring countries such as Bangladesh.

Sample this: international main line operators (MLOs) – like Maersk, Hyundai and HapagLloyd – that carry goods from the US, the EU and other countries do not unload the Bangladesh-bound goods at the Indian ports.

Rather, the MLOs take the Bangladesh-bound goods to other transhipment hub ports like Singapore, Colombo or Kelang, where they are stacked in the terminals for at least a month before they are carried to Bangladesh in small vessels.

India’s landscape

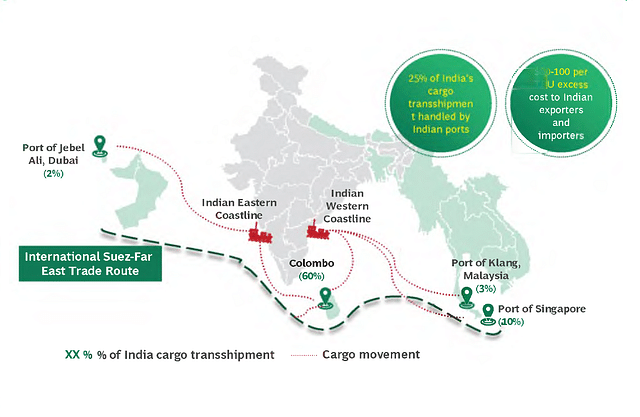

Around 75 per cent of India’s container traffic is gateway containers (which operate directly from the port of origin to the port of destination), while 25 per cent are transhipped enroute to the destination.

Currently, nearly 75 per cent of India’s transhipped cargo is handled by transhipment hub ports such as Colombo (and now, also, Hambantota), Singapore, Salalah (Oman), Jebel Ali (DP World’s flagship port in Dubai), and Tanjung Pelepas and Port Klang (Malaysia).

The Ports of Colombo, Singapore, and Klang handle more than 85 per cent of this cargo, with 45 per cent of this cargo handled at Colombo Port, according to Ministry data.

Essentiality

The dependence on foreign ports is a disadvantage for three reasons.

One, Indian ports lose up to $200-220 Mn of potential revenues each year on transhipment handling of cargo either originating or destined for India.

The loss is even higher when considering the opportunity to handle cargo emerging from other countries in the region is considered.

Two, transhipment adds to the cost incurred by the Indian industry. The transhipment cost also leads to higher logistics cost to the shipper, where the additional freight and handling cost get loaded to the overall cost.

Apart from the cost of the feeder voyage to and from Indian ports to the transhipment hub, which is unavoidable, the additional port handling cost to the tune of $ 80-100 per TEU – at the hub also gets added to the transhipped cargo.

This cost could be saved if the container was imported or exported as direct gateway cargo instead of being transhipped.

Three, with increasing Chinese influence through massive investment in port infrastructure in the Indian Ocean as part of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), dependence on foreign ports is a potential national security challenge.

For example, China Merchants Port Holdings (CMPort) has invested in the Colombo Port South Container Terminal. Moreover, Sri Lanka has launched a project to build the largest commercial and logistics complex in South Asia at the Port of Colombo with a pledged investment of 392 million U.S. dollars from CMPort.

To put this in perspective, such a dependency makes Indian industries vulnerable to increase in costs, potential inefficiencies, and congestion issues, and creates long term risks for India’s trade competitiveness

Therefore, developing a major transhipment hub in India is a necessity.

Enabling a transhipment hub in India will not only address the current revenue losses for Major ports but also help take advantage of an attractive position on global maritime routes.

A good transhipment port in India would not only facilitate the movement of its own originating and destined traffic but also play a pivotal role in handling traffic along the major routes connecting India, such as traffic between the US/Europe and the Indian subcontinent, US/Europe and the Far East, and Africa and the Far East.

Identified Hubs

The Maritime India Vision (MIV) 2030 envisages developing transhipment hub at four location – Vizhinjam, Kanyakumari region, Andamans and Cochin Port – in Southern India in a phased manner

Out of this, ports at Kochi and Vizhinjam in Kerala as well as Galathea Bay in Andaman Nicobar Islands have made a headway in the direction of becoming transhipment hubs.

The Vizhinjam International Port, hardly 11 nautical miles away from the international shipping channel, will be India’s first international deepwater transhipment port.

It has a natural draft of more than 18 meters, scalable up to 20 meters, which is crucial to get large vessels and mother ships. As per the latest work schedule, the first phase of the project is slated to be operational in May 2024.

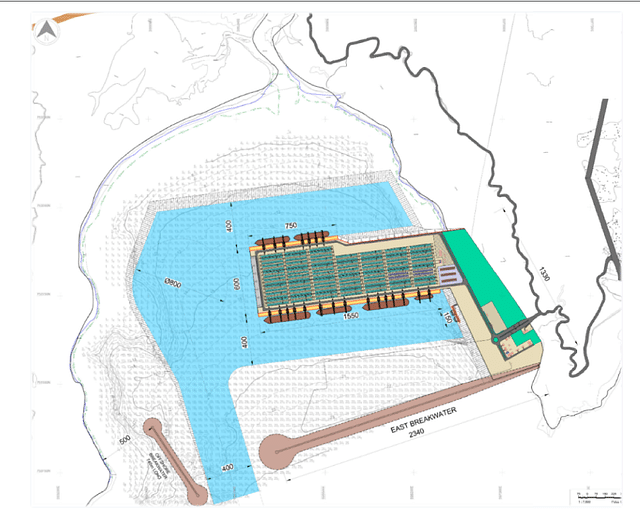

Similarly, the Rs 48,000 crore Great Nicobar Port which will come up at Galathea Bay in Great Nicobar Island of the Union Territory of Andaman and Nicobar Islands, is currently under pre-tender stage.

The port facilities are proposed to be developed in four phases between 2028 and 2058 and would handle 16 million containers per year, in the ultimate stage of development.

The first phase, upon completion in 2028, will handle 4 million containers per year. In January 2023, the Shipping Ministry had invited expressions of interest (EoIs) for develop the first phase of ICTP project.

Notable names that have submitted EoIs for the project include Adani Ports, JSW Infra, Rail Vikas Nigam Ltd (RVNL), and Container Corporation. On the international front, Dutch dredging major Royal Boskalis Westminster has expressed its intent to be included in the bidding process.

Further, the Union government has started the leg-work to develop Vallarpadam International Container Transhipment Terminal (ICTT) at Cochin Port into a successful international transhipment hub in the region — to position as a competitor to Colombo — and to attain self-reliance in container transhipment.

Towards this end, the ports ministry had recently given in-principle approval to Cochin Port Authority (CPA) for deepening draft depth at Vallarpadam ICTT.

Both Vizhinjam and Galathea Bay port have deep draft potential of around 20m, and are also promising locations given their position at approximately 6-10 Nautical Miles (NM) deviation (0.5-1 hours) from the Suez route, a fact that makes them look attractive to liners.

The Suez route accounts for a significant share of the total global container traffic flows, and the mainline vessels use this route for transporting cargo between the US, Europe and Asia.

However, despite their potential to compete with leading global transhipment hubs like Colombo and Singapore, competitive pricing and turnaround time will remain critical to attracting traffic.