The first phase of the under-construction Vizhinjam international container transhipment port in Kerala will be fully commissioned by May 2024, Vizhinjam Port CEO and MD Rajesh Jha has said.

He shared the project opening timelines while addressing the India Today Conclave South 2023,

“Our journey has not been easy, it was practically impacted by everything that could impact us. From cyclones to superfloods and then the pandemic. In spite of that, we are talking about the completion of the port. The first phase, which is 800 metres of berth and practically 3,000 meters of breakwater, should be ready by May 2024,” he said.

Karan Adani, Chief Executive Officer, Adani Ports and Special Economic Zone Ltd (APSEZ), had earlier confirmed the project commissioning schedule during an analysts call last week after the company announced the fourth quarter results.

APSEZ, which is part of the Adani Group, is responsible for the construction, operation and maintenance of the port,

“We expect the first vessel to berth in October this year, that’s when we expect the first equipment to come. We expect the Phase 1 of the port (400 metre quay) to be commissioned by March 2024 and the balance by May 2024. So, we expect the full commissioning of of Vizhinjam Port by May 2024,” Adani said.

The deepwater, multipurpose, international seaport and container transhipment terminal at Vizhinjam is expected to significantly boost India’s maritime trade ambitions.

The Significance Of The Vizhinjam Port Project

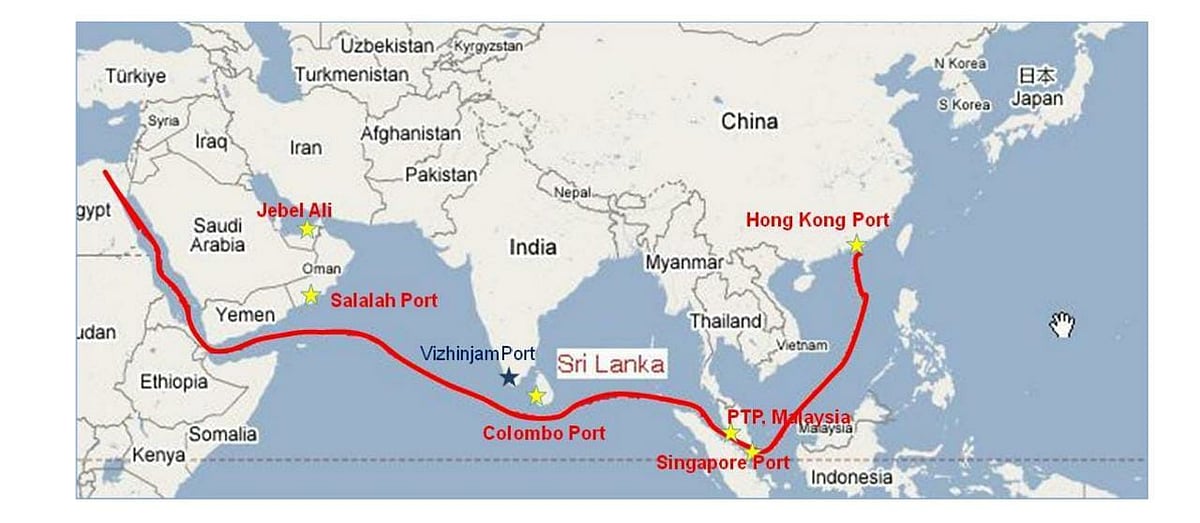

Most of India’s container traffic business is currently handled by transhipment hub ports such as Colombo, Singapore, Salalah (Oman), Jebel Ali (DP World’s flagship port in Dubai), and Tanjung Pelepas and Port Klang (Malaysia).

While India, with a coastline of about 8,000 km dotted with over 200 ports (including 13 major ports), most of them are of shallow depth, ranging from just nine metres to 11 metres, and cannot accommodate the kind of massive ships that are now a standard feature of transnational trade.

The biggest ships linking Europe and the Far East cannot dock at any Indian port. India lacks container transhipment infrastructure capable of servicing them. Only a handful of ports, including Mumbai, Mundra, Kochi/Vallarpadam, Chennai and Visakhapatnam have container handling facilities.

It is in this context that Vizhinjam port assumes huge significance.

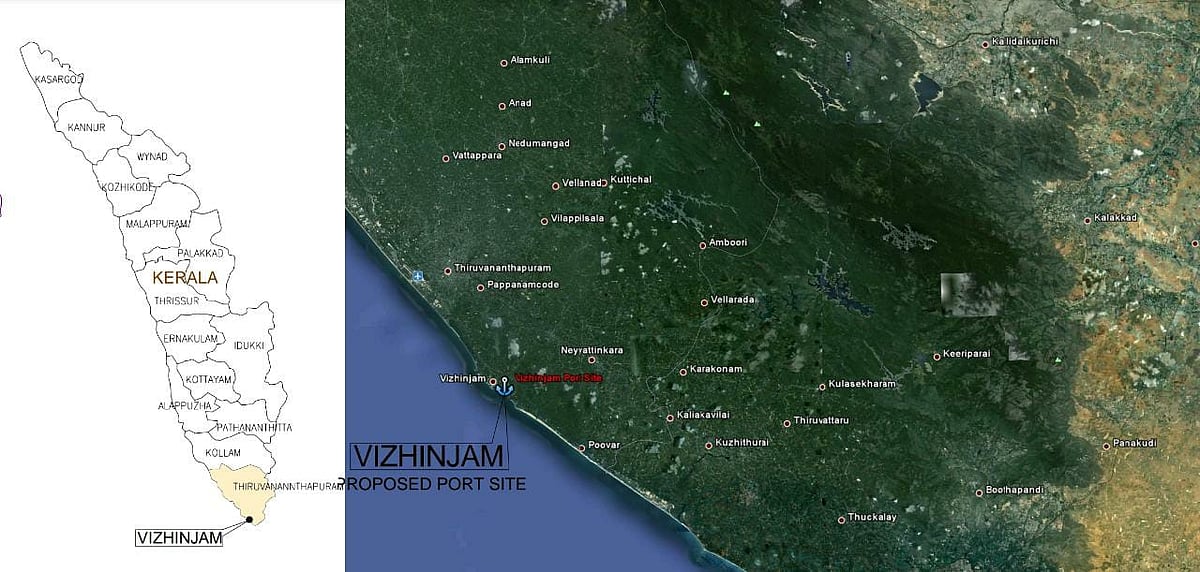

Vizhinjam, located about 14 km from Kerala’s capital city of Trivandrum, has a natural depth of over 18 m and is located hardly ten nautical miles (18 km) from the international shipping route from West Asia, Africa and Europe to the far eastern regions of the world.

Additionally, the availability of a 20-metre contour within one nautical mile from the coast, minimal littoral drift along the coast, the natural depth that excludes the need for maintenance dredging, potential for better road, and rail transport link potential make Vizhinjam a strategic well-suited for the greenfield project.

Vizhinjam is envisaged to be an all-weather, multipurpose, deepwater, mechanised, greenfield port that seeks to garner the lion’s share of the Indian transhipment cargo now being handled by the nearby foreign ports and emerge as the future transhipment hub of the country.

Once phase 1 becomes operational, Vizhinjam port is projected to handle 1 million TEUs ( 20-foot equivalent container units), and in subsequent phases, another 6.2 million TEUs will be added, which makes up over 70 per cent of the country’s current transhipment.

Phase 1 of the seaport project involves building a 3.1-kilometre breakwater, an 800-meter container berth to accommodate two 12,500 TEU (twenty-foot equivalent unit) container vessels and a fishing harbour.

Funding Model

The port is currently being built under a landlord model with a Public Private Partnership component on a design, build, finance, operate, and transfer (DBFOT) basis.

The Central and State governments together are providing a grant of Rs.1,635 crore (about 40 per cent of the project cost) under the Viability Gap Funding (VGF) scheme for public-private projects (PPP). VGF is a government grant provided to support infrastructure projects viewed as ‘economically justified but fall short of “financial viability”.

The Adani Ports and Special Economic Zone Ltd (APSEZ), which quoted the least VGF grant, was awarded the project in 2015

The concession agreement for the port project was signed during the tenure of the Congress-led UDF government led by Chief Minister Oommen Chandy.

As per the signed agreement, Adani Group will have the sole right to operate the port under licence initially for 40 years and, then, for an additional 20 years if the second phase of the project is built by the group at its own expense within the first 30 years.

The Kerala government is expected to spend about Rs.3,436 crore for basic infrastructure civil works such as the breakwater, quay wall, dredging, reclamation, rail and road access to the port.

The Kerala government will collect a premium revenue share from the private operator from the 16th year of operations, equivalent to 1 per cent of the gross revenue from the facility. The premium collected from the private operator will rise by 1 per cent every year till it reaches 40 per cent.

When construction began on December 5, 2015, group chief Gautam Adani said that the first ship would berth there on September 1, 2018, in a record time of less than 1,000 days.

Cyclone Okchi devastated the region in 2017, destroying a portion of the built breakwater. Since then, a further delay has been brought on by the lack of limestone, the project’s most crucial raw material.

The port also encountered persistent opposition from the nearby fishing communities and Church groups, who claimed that the construction and debris negatively influenced their ability to find fish and, consequently, their livelihoods.